The Fallout Factor in

Targeting Iran’s Nuclear Program

Doreen Horschig and Bailey Schiff / Center for Strategic and International Studies

(June 23, 2025) — On June 19, Israeli military spokesman Brigadier General Effie Defrin mistakenly stated that the Israel Defense Forces had struck Iran’s Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant. Although Israel quickly walked this back, the comment triggered regional alarm: Oman circulated information to civilians on what to do in the event of a nuclear incident, Bahrain prepared 33 shelters in case of an emergency, and the Gulf Cooperation Council activated its Kuwait-based Emergency Management Centre.

This reaction underscores a deeper concern quietly influencing the Israeli and US campaign: how radioactive fallout risks shape the limits of military action against Iran’s nuclear program.

Russia and China have seized on the confusion, falsely asserting that the targeting of any nuclear site risks catastrophic contamination. While Moscow’s and Beijing’s claims exaggerate the risks, they also tap into legitimate concerns: Some nuclear targets do carry significant fallout risks. Understanding these risks can help explain both why Israel has avoided some sites and the challenge of completely dismantling Iran’s nuclear program militarily.

While contamination concerns are not the central driver of Israeli strategy toward Iran’s nuclear program, in the next stage of the conflict, they may increasingly influence Israel’s target selection, timing, and operational methods. Israel now has fewer viable military options left for striking Iran’s nuclear program.

With US and Israeli attacks targeting portions of Natanz, Fordow, and Isfahan, what remains are either sites like Bushehr—which carry high radiological risk—or the remaining hardened underground facilities at Fordow, which would demand significant escalation to neutralize.

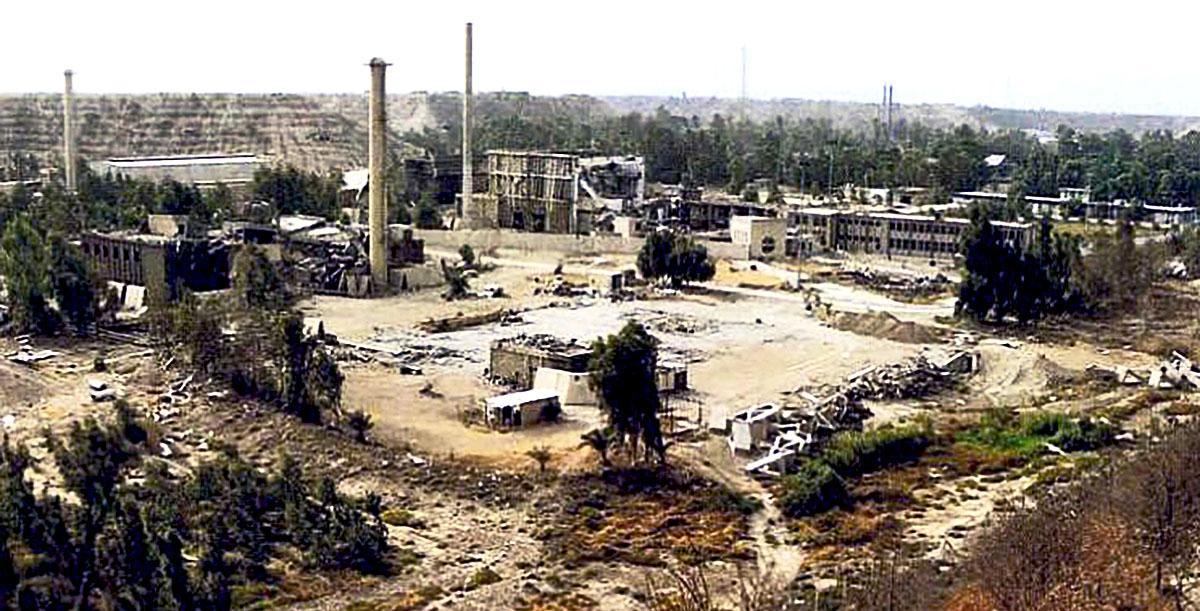

The aftermath of Israel’s bombing of Iraq’s Osirak reactor.

When Preemption Was Simpler: Israel’s

Historic Counterproliferation Strikes

Historically, Israel has both taken precautions to protect civilians and used environmental and contamination concerns to justify preventive strikes before neighboring nuclear programs went online, as evidenced by declassified documents from Israel’s attacks on the Iraqi and Syrian nuclear reactors in 1981 and 2007, respectively.

During Operation Opera on Iraq’s Osirak reactor, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin argued that waiting until the reactor was active would cause contamination. Similarly, a US State Department memo highlights that the Israelis expressed the “desire to avoid the radiation problem which would have occurred once the reactor was charged.”

In the 2007 strikes on the Syrian Deir ez-Zor reactor (Operation Orchard), Israeli officials cited the proximity to the Euphrates River as part of their rationale for attacking before it was operational. Although environmental concerns were a factor in both cases, fallout was avoided because preemption simplified the mission.

Today, dismantling the remainder of Iran’s nuclear program presents a more complex challenge: Its more sensitive facilities are already active, highly fortified (requiring heavier munitions), and striking with large quantities of radiological and chemical material does present genuine contamination risks.

Operation Midnight Hammer, the June 21 US strikes on Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan, may represent the ceiling of what conventional force can achieve on Iran’s nuclear targets without triggering broader fallout. For Israel, this means that future operational phases would have to involve sites that are either more fortified, environmentally risky, or both. As the campaign moves forward, Israel will have to balance its goal of complete dismantlement with the potential for fallout in ways it has not had to before.

Evaluating Fallout Risks: What’s Been Hit,

What’s Off-Limits, and What’s Left

The radiological and chemical risk from military strikes on Iranian nuclear infrastructure vary dramatically based on the type, operational status, fortification level, and dispersal potential of the facility (Table 1)

Bushehr, Tehran, and Arak Reactors

Attacking large operational light water reactors like the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant would pose the greatest contamination risk due to high inventories of radioactive materials in spent fuel. A direct hit or destruction of powerlines could trigger a meltdown, releasing iodine-131 and cesium-137 likely throughout Iran and to nearby Gulf states, potentially even compromising desalination infrastructure in Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates.

The Tehran Research Reactor, while also a light water reactor, presents a more localized risk that would be confined to Iran’s capital city due to its smaller scale and lower fuel inventory.

In contrast, heavy water reactors like Arak would pose the lowest radiological risk because they operate at lower pressures and contain less volatile waste. However, if attacked and active, they can release heavy water into the surrounding environment or create hydrogen explosions. Israel’s recent strike on Arak did not cause any contamination because it was unfinished and nonoperational.

Natanz and Isfahan. Strikes on enrichment facilities and uranium conversion plants pose some chemical hazards that could be contained within the facilities with limited radiological risks. The main concern for both the Natanz enrichment plant and Isfahan Uranium Conversion Facility is the presence of highly enriched uranium stockpiles and fluoride compounds used to convert yellowcake into gaseous uranium hexafluoride.

After the Israeli strikes last week on both sites, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) confirmed contamination within both facilities but noted that there was no elevation in chemical or radiation levels outside either site. Most chemical risks at these facilities can be mitigated through the provision of protective equipment for personnel.

Fordow. Buried about 300 feet underground near the city of Qom is the Fordow enrichment plant, Iran’s most fortified target and the most difficult to completely dismantle conventionally. During Operation Midnight Hammer, B-2 Spirit Bombers dropped 12 GBU-57 bunker-buster bombs on the facility, demonstrating the most powerful conventional aerial strike option.

This strike poses some risk of localized contamination if it breaches subsurface materials, but the potential for dispersal is modest due to its depth, isolated location, and its status as an enrichment facility, which means the fallout risks would be chemical as opposed to radiological.

Although President Trump claimed “complete and total obliteration” of the facility, early satellite imagery suggests only partial damage, and US officials, including Vice President JD Vance, have refused to confirm that the facility was destroyed. Without IAEA access to the sites, it could be a while until the full extent of the damage is known.

Another factor influencing radiological contamination in future strikes would be the presence of Iran’s highly enriched uranium stockpile, which is believed to have been dispersed to covert locations across the country. US officials have expressed that the stockpile’s whereabouts are unknown, but under Iranian control. Should either US or Israeli strikes target that 60 percent stockpile above ground (either on purpose or inadvertently), there could be localized radiation effects.

Operation Midnight Hammer likely tested the limits of how much can be destroyed without resorting to tactical nuclear weapons that could trigger broader environmental consequences, but the fallout risks likely are shaping, and will continue to shape, what remains militarily viable for Israel.

Iran’s Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant is run by Russian operators.

Implications for Israeli Military Strategy

Environmental considerations, particularly concerning radioactive fallout, seemingly play a secondary but not insignificant role in shaping Israel’s current strategy against the Iranian nuclear program.

Unlike the minimal environmental risks that the Syrian and Iraqi reactors presented, the operational Bushehr plant presents a far greater danger of widespread contamination if struck. Now that Israel and the United States have struck portions of Iran’s main enrichment facilities at Fordow and Natanz, Bushehr may become more important if Iran decides to explore a plutonium-based nuclear weapon.

Iran currently is required to send spent fuel rods to Russia, but it could stop doing so and instead attempt to retain and reprocess the fuel. However, despite the fact that Iran previously conducted plutonium reprocessing experiments in the 1990s, it is believed to lack the reprocessing capabilities to separate plutonium on a large scale, declaring to the IAEA that it abandoned reprocessing in 2003.

While Israel likely factors environmental risks into its targeting calculus of Fordow, these concerns are more likely to influence target selection, choice of munitions, and timing of strikes rather than dissuade action altogether.

If Operation Midnight Hammer failed to fully neutralize the enrichment hall, covert uranium storage areas, or other materials, the remaining options would narrow considerably and grow far more dangerous. Should Fordow remain at least partially operational, subsequent attacks will likely hinge on what level of destruction Israel and the United States view as acceptable, both in terms of military effectiveness and contamination risks.

The lowest risk of contamination, but most dangerous for Israeli soldiers, would be a ground operation involving infiltrating and planting explosives in the facility. Such an operation would result in contamination within the facility but is unlikely to spread to surrounding areas due to its depth.

The more alarming (and unlikely alternative) would be a tactical nuclear strike, which US defense officials were reportedly briefed could be the only guarantee of fully destroying the facility. With sabotage and special unit operations carrying the least environmental risk, they become strategically the most effective option, as well as the politically and diplomatically most palatable option. The use of any nuclear weapon against Fordow by Israel or the United States would carry high risks.

The cumulative effect of Israel’s considerations of environmental risks serves as a filtering mechanism in its target selection. Facilities that pose high risks of contamination but lower strategic value, like Bushehr, are likely to be avoided. Those with moderate environmental risk but high potential to contribute to proliferation, like Fordow, remain prime targets, but with the attempt to keep fallout contained.

What Comes Next in Israel’s Campaign?

Israel’s military playbook for targeting Iran’s nuclear program is narrowing. After hitting key sites like Natanz, Fordow, and Isfahan, the remaining targets either pose extreme fallout risks, like Bushehr, or require escalatory measures to destroy fully, as with the fortified Fordow facility.

So far, Israel and the United States have avoided major contamination in their attacks, but doing so has required surgical precision, careful sequencing, and clear lines around what is off-limits.

The next steps are becoming more dangerous. Any follow-on strike on Fordow risks either significant contamination or increased exposure for Israeli personnel if the state engages in a ground operation. Hitting Bushehr, if Iran shifts toward a plutonium path, would cross a threshold that could trigger regional environmental fallout. Israel’s past campaigns relied on striking before reactors were operational. That option no longer exists.

Unlike legal or diplomatic objections, contamination risks may be starting to define the outer limits of what preventive counterproliferation can realistically achieve. The avoidance of Bushehr and the challenges of fully dismantling Fordow without escalation suggest that environmental concerns, rather than international pressure, could quietly be steering Israeli strategy. Whether this dynamic continues to constrain future operations remains to be seen.

Doreen Horschig is a fellow with the Project on Nuclear Issues at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, DC. Bailey Schiff is a program coordinator and research assistant with the Project on Nuclear Issues at CSIS.

Commentary is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2025 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes