Raytheon has made billions in sales to the Saudi coalition.

Michael LaForgia and Walt Bogdanich / The New York Times

16, 2020) — Year after year, the bombs fell — on wedding tents, funeral halls, fishing boats and a school bus, killing thousands of civilians and helping turn Yemen into the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

Weapons supplied by American companies, approved by American officials, allowed Saudi Arabia to pursue the reckless campaign. But in June 2017, an influential Republican senator decided to cut them off, by withholding approval for new sales. It was a moment that might have stopped the slaughter.

Not under President Trump.

With billions at stake, one of the president’s favored aides, the combative trade adviser Peter Navarro, made it his mission to reverse the senator. Mr. Navarro, after consulting with American arms makers, wrote a memo to Jared Kushner and other top White House officials calling for an intervention, possibly by Mr. Trump himself. He titled it “Trump Mideast arms sales deal in extreme jeopardy, job losses imminent.”

Within weeks, the Saudis were once again free to buy American weapons.

The intervention, which has not been previously reported, underscores a fundamental change in American foreign policy under Mr. Trump that often elevates economic considerations over other ones. Where foreign arms sales in the past were mostly offered and withheld to achieve diplomatic goals, the Trump administration pursues them mainly for the profits they generate and the jobs they create, with little regard for how the weapons are used.

Mr. Trump has tapped Mr. Navarro, a California economist best known for polemics against China, to be a conduit between the Oval Office and defense firms. His administration has also rewritten the rules for arms exports, speeding weapon sales to foreign militaries. The State Department, responsible for licensing arms deals, now is charged with more aggressively promoting them.

“This White House has been more open to defense industry executives than any other in living memory,” said Loren B. Thompson, a longtime analyst who consults for major arms manufacturers.

No foreign entanglement has revealed the trade-offs of this policy more than the war in Yemen. There, Mr. Trump’s embrace of arms sales has helped prolong a conflict that has killed more than 100,000 people in the Arab world’s poorest nation, further destabilizing an already volatile region, according to a review of thousands of pages of records and interviews with more than 50 people with knowledge of the policy or who participated in the decision-making.

American arms makers who sell to the Saudis say they are accountable to shareholders and are doing nothing wrong. And because weapon sales to foreign militaries must be approved by the State Department, the companies say they don’t make policy, only follow it.

But as the situation in Yemen worsened, at least one firm, Raytheon Company, did more than wait for decisions by American officials. It went to great lengths to influence them, even after members of Congress tried to upend sales to Saudi Arabia on humanitarian grounds.

Raytheon, a major supplier of weapons to the Saudis, including some implicated by human rights groups in the deaths of Yemeni civilians, has long viewed the kingdom as one of its most important foreign customers.

After the Yemen war began in 2015 and the Obama administration made a hasty decision to back the Saudis, Raytheon booked more than $3 billion in new bomb sales, according to an analysis of available US government records.

Intent on pushing the deals through, Raytheon followed the industry playbook: It took advantage of federal loopholes by sending former State Department officials, who were not required to be registered as lobbyists, to press their former colleagues to approve the sales.

And though the company was already embedded in Washington — its chief lobbyist, Mark Esper, would become Army secretary and then defense secretary under Mr. Trump — Raytheon executives sought even closer ties.

They assiduously courted Mr. Navarro, who intervened with White House officials on Raytheon’s behalf and successfully pressured the State Department, diminished under Mr. Trump, to process the most contentious deals.

They also enlisted the help of David J. Urban, a lobbyist whose close ties to Mr. Esper and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo go back to the 1980s, when all three men were at West Point.

As the nation turned against the war, a range of American officials — Democratic and Republican — tried three times to halt the killing by blocking arms sales to the Saudis. Their efforts were undone by the White House, largely at the urging of Raytheon.

Approached a half-dozen times, Raytheon representatives declined to speak with reporters about foreign sales. “We believe further dialogue regarding foreign military sales is best directed to officials in the US government,” Corinne Kovalsky, then a company spokeswoman, said in December.

Lawmakers from both parties have condemned the continued arms sales in the Yemen war, expressing both humanitarian and security concerns: Some of the weapons have wound up in the hands of militant Islamic groups in the country.

“We don’t know how these weapons are really being used or whether they may be turned against US troops in the future,” said Senator Mike Lee, Republican of Utah, who has publicly criticized the administration’s approach to the conflict. “This war was never authorized by Congress.”

Others say the president’s arms sale policies diminish the United States.

“People look to us. We’re the only country in the world that is ever capable of using this immense power that we have in a way that’s more than just about our naked self-interest,” said Representative Tom Malinowski, a New Jersey Democrat who was born in Communist Poland and led the State Department’s human rights bureau under President Barack Obama.

“President Trump has proudly said that we should continue to sell weapons to Saudi Arabia because they pay us a lot of money,” Mr. Malinowski said. “He seems to see foreign policy in the way he viewed the real estate business — every country is like a company and our job is to make money.”

The Trump administration has defended arms sales to Saudi Arabia as being vital to job growth and the American economy.

“We’ve created an incredible economy,” Mr. Trump told Fox Business in October 2018, after the killing of the journalist and American resident Jamal Khashoggi sparked calls to stop selling to the Saudis. “I want Boeing and I want Lockheed and I want Raytheon to take those orders and to hire lots of people to make that incredible equipment.”

Raytheon hired former U.S. officials to press for approval of arms deals with Saudi Arabia, one of its most important clients.Credit…Pascal Rossignol/Reuters

Records show that foreign military sales, facilitated by the US government, rose sharply after Mr. Trump became president. They averaged about $51 billion a year during Mr. Trump’s first three years, compared with $36 billion a year during the final term of Mr. Obama, who also oversaw a big increase.

Arms industry groups say defense jobs rose more than 3.5 percent to about 880,000 during Mr. Trump’s first two years, though the numbers, the most recent available, do not specify how many were in manufacturing.

The White House referred requests for comment to the National Security Council, where a spokesman said that “Iran and its Houthi proxies” had targeted Saudi Arabia and had endangered Americans. “We remain committed to supporting Saudi Arabia’s right to defend against those threats, while urging that all appropriate measures are taken to prevent civilian casualties,” said the spokesman, John Ullyot.

A State Department spokeswoman said that the administration had made clear that “economic security is national security,” and that the administration was “strengthening our advocacy for defense sales that are in our national interest.” She disputed the suggestion that human rights had taken a back seat to other considerations, insisting the new approach “actually increases focus on human rights” through military training and other programs with allies.

Anthony Wier, a former State Department official under Mr. Obama, said past administrations of both parties had sought to balance the economic benefits of arms sales with the realities on the ground.

“This is an important export industry with a lot of factory jobs, with a lot of states,” Mr. Wier said. “But there’s also a crater in Yemen where a school bus used to sit, and there’s a stack of children dead.”

Getting the President’s Ear

Mr. Trump won the presidency partly on promises to resuscitate American manufacturing.

“We’re going to bring back the jobs that have been stolen from you,” he told a packed arena in Raleigh, N.C., on Nov. 7, 2016, the day before the election. “We’re going to bring back the miners and the factory workers and the steelworkers. We’re going to put them back to work.”

But as the initial glow of victory faded, reality set in. Mr. Trump’s aides realized there were not many ways the executive branch, on its own, could affect manufacturing and trade, three former Trump administration officials said.

One campaign adviser, Mr. Navarro, thought he had a solution. A Harvard-educated economist, Mr. Navarro had published papers on management strategy and a book of investment advice, “If It’s Raining in Brazil, Buy Starbucks.”

He had not specialized in the American arms industry. Even so, he made the case to members of Mr. Trump’s transition team, including Stephen K. Bannon, then one of Mr. Trump’s most trusted advisers, that invoking national security and promoting the defense industry were ways to impose tariffs, create manufacturing jobs and shrink the trade deficit. Mr. Bannon embraced the pitch, according to a person with knowledge of the conversations.

In December 2016, the president-elect named Mr. Navarro head of the newly created National Trade Council, an ill-defined position that seemed in conflict with other, more established roles in the White House. And though the organization apparently existed only on paper, the title afforded him access to Cabinet-level meetings, where he would forcefully argue his points as the principals looked on.

Mr. Trump gave him responsibility for stoking American defense manufacturing by growing foreign arms sales, among other things. Defense companies took notice.

After Mr. Trump’s inauguration, representatives of Raytheon and other firms streamed in to see Mr. Navarro, finding him ready to listen. Mr. Navarro’s hard-line stance toward China was well known, and they played it to their advantage, said Mr. Thompson, the analyst and consultant, who soon arranged a lunch meeting between Mr. Navarro and industry leaders, including Thomas A. Kennedy, then Raytheon’s chief executive and now its executive chairman.

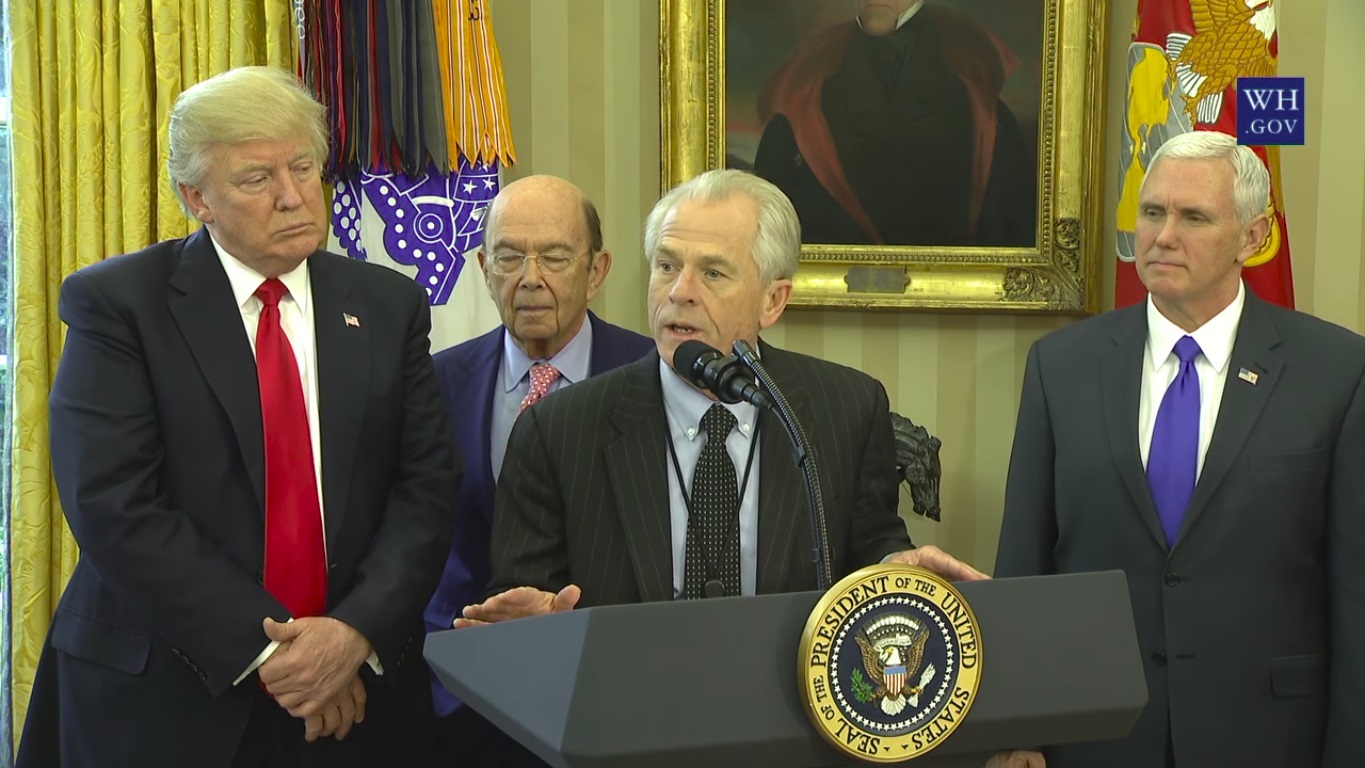

Mr. Trump in the Oval Office with Mr. Navarro, an economist who previously worked on the 2016 campaign. (Photo: Doug Mills/The New York Times)

The defense firms presented themselves as the rare high-tech industry that had not recently lost ground to China, Mr. Thompson said.

During the first years of Mr. Trump’s presidency, as aides undermined one another and turned over on a regular basis, Mr. Navarro’s claim to an essential mission, and his new ties to arms executives, insulated him from the turbulence, according to the former administration officials.

In Mr. Navarro, they said, the companies had an advocate who was not shy about confronting senior leaders over matters he deemed important. And while the officials often bristled at his presumption, and worked to marginalize him, Mr. Navarro nevertheless retained influence with Mr. Kushner and Mr. Trump.

Mr. Trump relished having around him an Ivy League economist who agreed with his pronouncements on trade. The president, in turn, listened when Mr. Navarro repeatedly raised arms sales to Saudi Arabia and other countries, sometimes repeating talking points used by Raytheon and other arms makers, the former administration officials said.

In an interview, Mr. Navarro said that his focus has been on carrying out Mr. Trump’s economic policies, not on corporate cheerleading.

“I don’t advocate for companies,” Mr. Navarro said. “I advocate for the president and for American workers and for our men and women in uniform. That’s it. Period. Full stop.”

Mr. Trump’s aggressive arms sale policies were met with alarm by some in the State Department, in part because the administration did not seem concerned with human rights issues, according to several current and former State Department officials, who like others interviewed for this article were not authorized to speak publicly. Though past administrations had sometimes shown a willingness to achieve narrow goals by arming rough regimes, Mr. Trump seemed to view weapon sales as ends in themselves.

Worse, they said, were signs of how little the administration grasped the basics of arms deals, which can have profound foreign policy and national security consequences.

One episode in spring 2017 underscored those concerns. When Mr. Kushner and others wanted to line up military sales ahead of a visit by Mr. Trump to Saudi Arabia, they convened meetings at the White House but did not invite the State Department — the only agency by law that can authorize foreign deals.

Arms sale specialists in the State Department learned about the gathering only after a senior Pentagon official called and urged them to hurry over, current and former officials said.

A $5 Billion Turnaround

As war broke out five years ago in Yemen, Raytheon was a company on the rebound.

Based in Waltham, Mass., it had risen over the years to become the third-largest defense firm in the United States, bolstered by sales of its best-known system, the Patriot missile. But Raytheon had been battered by flagging profits and federal budget cuts, and Mr. Kennedy, the chief executive, was determined to turn things around, starting with international sales.

Raytheon earned more of its revenue from sales to foreign governments than Lockheed Martin and other American defense giants, and few foreign customers were more important than Saudi Arabia. Its ties with the Saudis dated to the 1960s, when the company became one of the first American defense firms to build a permanent base in the kingdom.

Since then, generations of Raytheon executives had sought to ingratiate the company with the Saudis, hiring members of the royal family as consultants, building schools and investing in projects favored by the royal court.

The close relationship was evident two days after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, when three Saudi college students began their journey out of the country from Raytheon’s private terminal in Tampa, Fla., according to a report by the 9/11 Commission. (None of the men, including one who was a member of the Saudi royal family, was tied to the attacks, though Saudi nationals were among the hijackers.)

The longstanding ties helped Mr. Kennedy turn around the company. Since the Yemen war began, Raytheon has booked at least a dozen major sales to the kingdom and its partners worth more than $5 billion, US government records show, helping lift the firm’s fortunes and position it to pursue a merger with another large defense company, United Technologies, that was completed in April.

Some of the deals, for defensive items, sailed through the government approval process. But sales of offensive weapons, including more than 120,000 precision bombs and bomb parts that the Saudis were using in Yemen, faced major hurdles. Those deals were among the most lucrative ones, worth more than $3 billion, the government records show.

Rescue workers at the funeral hall that was bombed in Sana.(Photo: Mohammed Huwais/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images)

Trouble for the company started on Oct. 8, 2016, when Saudi coalition planes repeatedly targeted a funeral hall in Sana, the Yemeni capital, where some 1,500 men, women and children had gathered to mourn the father of a government official.

The first bomb shattered the building, killing some instantly and sending others on a scramble to escape the smoldering rubble. A second landed as people poured in to help the survivors. A third fell as the newly injured and dying were clambering amid the splintered wood and broken concrete.

“People were on fire, and some people were burned alive,” one survivor, 42-year-old Hassan Jubran, told human rights workers.

“There were also many children,” he said. “There were three children whose bodies were completely torn apart and strewn all over the place.”

At least 140 people died and another 500 were wounded in the bombing, which the Saudis later said was a mistake. Soon after the attack, human rights workers discovered amid the wreckage a bomb shard bearing the identification number of an American company: Raytheon.

It was one of at least 12 attacks on civilians that human rights groups would tie to the company’s ordnance during the first two years of the war.

Asked in 2017 whether dead and wounded civilians gave him pause, John D. Harris II, then Raytheon’s vice president of business development, told CNBC that they did not, “because we do the hard work of making sure that the countries that employ our systems have the very best training and the ability to use the system in an appropriate manner.”

The strike in Sana unsettled the Obama administration, which had agreed to support the Saudis but was becoming increasingly concerned about the war. “That demanded a response,” said Andrew Miller, a Middle East expert on Mr. Obama’s National Security Council. “By that time it was clear that the war had gone in a direction we had not anticipated.”

In December, the administration halted delivery of bomb parts that had been sold but not yet shipped, a decision that angered the Saudis and Raytheon. Mr. Kennedy placed a personal call to Mr. Obama’s national security adviser, Susan Rice. But the administration would not budge.

The firm would have to wait until Mr. Obama left office — and then try to forge ties with the Trump administration as quickly as possible.

The company’s executives got to work.

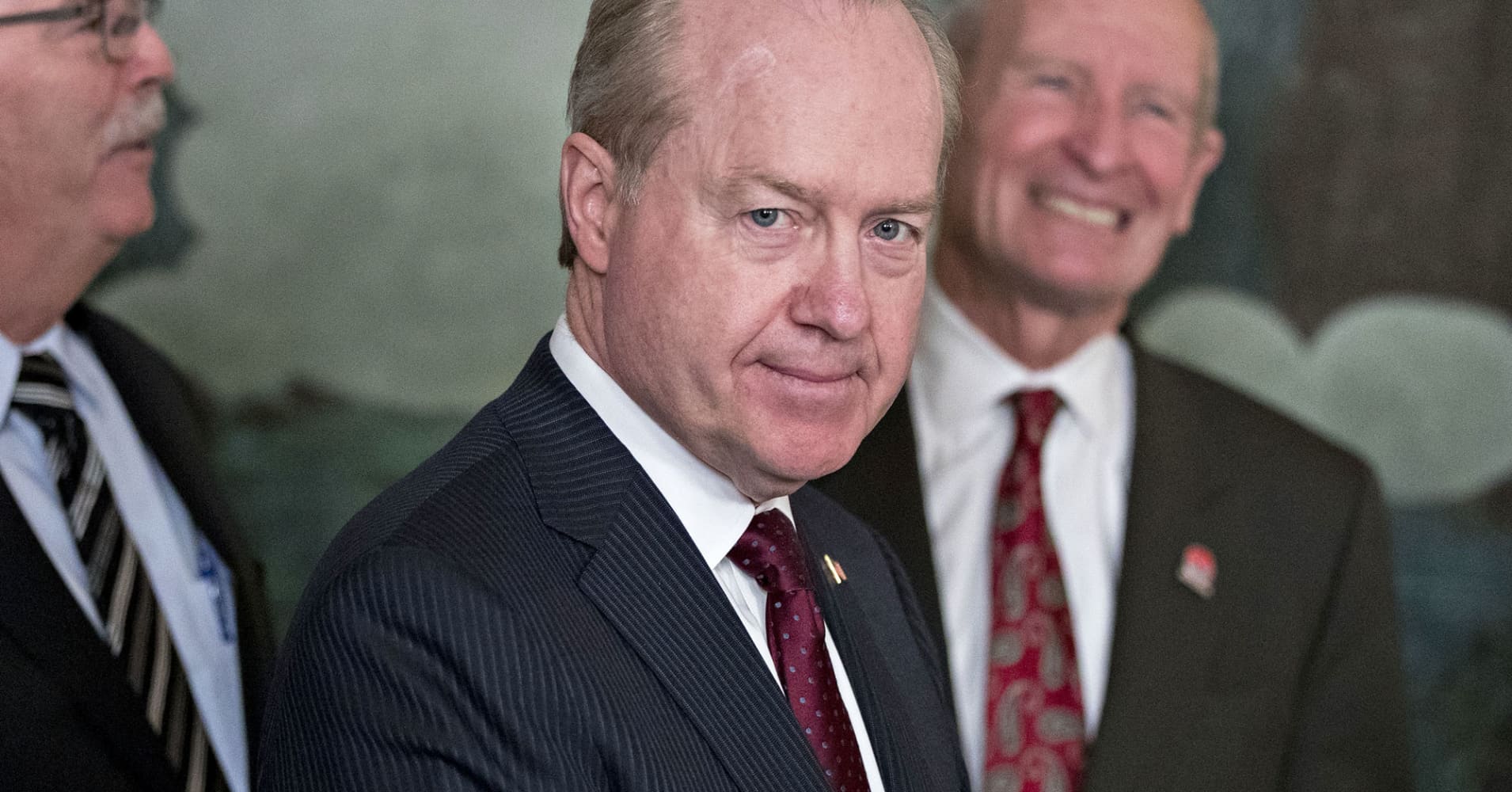

Thomas A. Kennedy, on a White House visit while he was chief executive of Raytheon (Photo: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg)

‘Raytheon, Congratulations’

Just seven months into the new administration, Mr. Kennedy was standing by Mr. Trump’s side in the White House, watching as the president dashed his signature across a presidential memorandum on trade with China.

When he was finished, Mr. Trump held up the pen. “Where’s Raytheon?” he asked. Mr. Kennedy leaned in to accept the gift.

“Raytheon,” Mr. Trump said, “congratulations.”

It was August 2017, and the Trump administration was in the grip of a crisis. Business leaders were abandoning the president over his comments about racial violence in Charlottesville, Va., just when he needed executives to show support for a new crackdown on China.

Mr. Kennedy was there to help Mr. Trump, even though his company had virtually no relationship with China. He did not get there by accident.

During the early months of the new presidency, Raytheon executives tried to get close to the administration by arranging for Mr. Kennedy to meet with Mr. Trump on a handful of occasions, including during the president’s trip to Saudi Arabia that May, former employees said.

Soon after the trip, the Trump administration waved through the delivery of bomb parts to the Saudis that Mr. Obama had delayed. But the company wanted more.

So it turned to Mr. Navarro, whose office helped Raytheon orchestrate Mr. Kennedy’s appearance at the August signing ceremony, according to a person with direct knowledge of the arrangement.

It was a face-saving moment for the president, and a turning point in the company’s relationship with the White House. In the months that followed, Mr. Navarro pushed hard for Raytheon and its deals with Saudi Arabia.

His first order of business was trying to reverse a new obstacle to the company’s deals — a decision in June by Senator Bob Corker, Republican of Tennessee, to block arm sales from Raytheon and other companies to Persian Gulf nations over a matter unrelated to the Yemen war. As chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Mr. Corker had the authority to place a hold on the deals.

The move put Raytheon in a difficult position. The company was already in contract to sell the Saudis and Emiratis more bombs and bomb parts for nearly $2 billion. But unlike the earlier deal that Mr. Obama had halted, these agreements exposed Raytheon to onerous penalties if the company did not deliver.

At first, Mr. Navarro directed his attention at Mr. Corker, complaining that the senator was interfering with the president’s agenda, one former White House official said. “It was clear that this for him was priority No. 1,” the official said of overturning the hold.

By that winter, Mr. Navarro had shifted his focus to Secretary of State Rex W. Tillerson, whose department, Mr. Navarro learned, had still not forwarded to Congress its approval for the Raytheon bomb deals — a crucial step for them to be finalized.

To break the logjam, Mr. Navarro sent the memo in January 2018 to top White House officials, urging them to bring Mr. Tillerson in line. Recipients included Mr. Kushner, who, like Mr. Trump, his father-in-law, enjoyed a close relationship with the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, and would have been sensitive to Saudi complaints about stalled weapon deals.

The memo was described by three current and former government officials; one read portions of it to a New York Times reporter.

It called for White House officials to “meet with Tillerson and direct him to immediately” send the pending deals to Congress for approval. Then, it continued, the White House should contact Mr. Corker to make sure he cleared the sales right away.

“Unless the White House promptly intervenes, one particular company, Raytheon, will begin laying off thousands of workers,” Mr. Navarro wrote, attributing the information to “industry sources.” He added: “POTUS may have to get involved,” a reference to Mr. Trump.

Mr. Navarro, in the interview, said he involved himself not because any company’s deals were at stake but because Mr. Tillerson was running a foreign policy that was not in line with Mr. Trump’s.

“When the president of the United States found out that his signature arms sales packages weren’t moving, he said, ‘Fix this.’ That’s what I do at the White House,” Mr. Navarro said. “I fix things.”

Within a week of the memo, Mr. Tillerson met with Mr. Corker. About three weeks later, the senator lifted the prohibition. Mr. Corker declined to comment.

Mr. Navarro’s memo landed as Mr. Tillerson’s relationship with the White House was deteriorating, and the delay in moving the Saudi sales deepened the rift at a critical moment, former officials said. Morale within the department was also flagging, and several senior leadership posts remained unfilled.

Tina Kaidanow, who oversaw the State Department’s arms sale approval bureau at the time, recalled cautioning Mr. Tillerson in a meeting.

“I told him that continuing to hold those sales would almost certainly occasion an unhappy response from a White House focused on increasing arms sales to Saudi Arabia,” Ms. Kaidanow said in an interview.

Mr. Trump fired Mr. Tillerson that March.

A Third Intervention Fails

Raytheon may have had a powerful White House ally who had influence over a Republican senator and an unpopular cabinet member. But the company’s sway did not extend to Democrats on Capitol Hill.

Weeks after Mr. Navarro helped end Mr. Corker’s hold, another leading senator blocked the Raytheon deals. Senator Robert Menendez, Democrat of New Jersey, made the third attempt to stop the arms feeding the Yemen war.

By then the fighting had entered its third year. The death toll had soared past 50,000, including 9,000 civilians, raising concerns among Mr. Menendez and other lawmakers that the Saudis were not doing enough to avoid killing noncombatants. Mr. Kennedy of Raytheon visited Mr. Menendez in the Capitol in May 2018, pleading his company’s case in an ornate room usually reserved for welcoming foreign dignitaries.

The senator, who as ranking member of the Foreign Relations Committee had authority to block the sales, was unswayed.

“I told him I don’t have an ideological problem; I have supported other arms sales. But you cannot, as a company, be promoting the arm sales to a country that is using it in violation of international norms,” Mr. Menendez said in an interview. “I understand the motivation for profit, but I don’t understand the motivation for profit in the face of human rights violations and civilian casualties.”

At the same time, the company’s Washington office deployed former State Department officials to press their former colleagues in the administration. Among them was Tom Kelly, the erstwhile American ambassador to Djibouti, a small country across the Gulf of Aden from Yemen.

It was a strategy common among defense contractors, who routinely bring on former government officials for their expertise and deep connections, said Mandy Smithberger, a defense analyst at the Project on Government Oversight, a watchdog group. A loophole does not require them to register as lobbyists.

“These people are being hired for who they know,” Ms. Smithberger said, calling the practice “a form of legalized corruption.”

Mr. Kelly did not respond to a request for comment.

Meanwhile, Mr. Navarro continued his push for Raytheon sales.

He had already overseen a rewrite of the government’s conventional arms transfer policy — its rules for selling arms to foreign militaries — to make it easier for companies like Raytheon to win government approval. The new rules, which marked the first time “economic security” was listed as a guiding principle, called for the State Department to expand its support of American defense firms abroad while paring back regulations that slowed the transfer process.

Mr. Navarro then began holding biweekly progress meetings about pending deals, including Raytheon’s, with officials from the National Security Council and the State Department.

During the meetings, he put intense pressure on officials to move the deals forward, according to two people present at some of the gatherings, asking over and over again: “Why aren’t we further along?”

Some State Department officials worried that a White House trade adviser with no foreign policy role was expediting arms sales with profound diplomatic consequences, the people present said.

Mr. Navarro, in his interview, said the meetings were necessary to “bring to heel a bunch of career bureaucrats” who were not carrying out the president’s wishes.

“We dramatically accelerated the pace of approvals on the Hill and at State to the advantage of American workers and the security of our allies and partners,” Mr. Navarro said.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo at a meeting last year with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia (Pool photo by Andrew Cabellero-Reynolds)

That fall, the C.I.A. implicated Prince Mohammed in the killing of Mr. Khashoggi, the American resident and Washington Post contributor, further damaging the kingdom’s standing with Congress. But pressure from Mr. Navarro and industry officials on the State Department kept building until spring last year, when Mr. Pompeo, who had replaced Mr. Tillerson as secretary of state after helming the C.I.A., decided it was time to move the sales through.

That April, Mr. Pompeo met with other top administration officials and discussed declaring an emergency to release the arms — something that had occurred only rarely in the past. Soon after, they decided to fast-track the sales by citing the need to counter Iran, which was supporting Yemen’s Houthi rebels, according to a person with knowledge of the meetings. A State Department spokeswoman declined to comment on specific deliberations.

Declaring an emergency would bypass Congress and risk alienating allies on Capitol Hill. Mr. Pompeo and the others pursued it anyway.

Only a handful of people within the Pentagon and State Department knew of the plan. They did not include anyone in the State Department’s human rights bureau, which had consulted on weapon sales in previous administrations, the person said.

Mr. Pompeo took the final step on May 24, 2019, the Friday before Memorial Day weekend, delivering Congress an emergency declaration tailored to free up more than 20 stalled deals, including Raytheon’s bomb sales, by citing Iranian support for the rebels in Yemen.

Within weeks, those arms were flowing again.

By the end of the year, the civilian death toll in Yemen had topped 12,000.

An attack in Jawf Province this February killed 32 civilians, mostly women and children. A bomb part tied to Raytheon was found in the rubble (Mwatana for Human Rights)

A Trap ‘Like Flypaper’

As Mr. Trump gears up for re-election, the administration has framed arms sales to the Saudis as a win, signaling no regrets. “The relationship has been very good, and they buy hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of merchandise from us,” Mr. Trump told reporters before boarding Marine One in October. “It’s millions of jobs.”

But for those who first pledged American support to the Saudis, the past five years have been replete with second-guessing and misgivings.

Officials in the Obama White House, recalling how the Saudis had sought American backing, know it as the “five minutes to midnight” call. It was late March 2015, and the Saudis wanted to know immediately whether the United States would support its imminent invasion of Yemen to suppress the Iranian-aligned rebels who had overthrown the Saudi-friendly government there. The Saudis characterized the military action as necessary to defend their borders from potential Iranian aggression, just as the United States was involved in negotiations with the Iranians over a nuclear deal.

“It happened so quickly,” Ben Rhodes, one of Mr. Obama’s foreign policy advisers, said in an interview. “Obama typically had a very rigorous process around certainly the application of US military force, and this felt very different.”

With few options, none of them appealing, the advisers recommended a high-risk plan to support a country with billions of dollars in American weapons but little experience in using them.

Mr. Obama agreed despite misgivings. Not wanting to get embroiled in another war, he offered primarily defensive support without defining in clear terms what that meant. The arms industry would later seize on the ambiguity to sell the Saudis billions of dollars in both offensive and defensive weapons.

On the day of the call, as Mr. Obama’s advisers departed the White House Situation Room, at least a few had a sinking feeling. “We knew we might be getting in a car with a drunk driver,” one adviser would later say.

Within hours, their fears became reality.

While the Saudi ambassador in Washington was briefing the media, Saudi planes were already over Yemen. In their first bombing run, around 2 a.m., the Saudis hit a residential area and killed 14 children. Through the night, neighbors pulled the dead and the living from the piles of stone that had once been their homes. Three of the children belonged to a man named Yasser Al-Habashi, who did not learn they had died until he awoke from a coma 13 days later.

As evidence mounted in the following months that civilian casualties were rising, the Obama White House chose not to aggressively rein in the Saudis.

“People make miscalculations all the time,” Steve Pomper, a former senior official on Mr. Obama’s National Security Council, said in an interview. “But it was striking to me as I reflected on my time in the Obama administration that it wasn’t just that we embarked on this escapade — it’s that we didn’t pull ourselves out of it.”

In an extraordinary move, 30 former senior Obama officials signed a public statement of regret in November 2018 for what turned out to be, they said, a blank check of support for the Saudi military.

Mr. Pomper defended the government officials who oversaw Saudi policy, calling them serious, humane people. “And yet we found ourselves locked into this terrible situation, unable to wrap it up, and handing it off to an administration that was going to handle it even worse than we did. And I wanted to understand why we did that.”

The result was a lengthy report published under the auspices of the International Crisis Group, a nonprofit organization devoted to conflict resolution. It said American arms sales acted “like flypaper in trapping the US in Yemen.” The phrase echoed President Eisenhower’s famous warning about the unseen political influence of the “military-industrial complex.”

Gerald M. Feierstein, a former US ambassador to Yemen under Mr. Obama who now works for the Middle East Institute, a think tank funded in part by the United Arab Emirates, said America should not turn its back on an important strategic ally, despite the civilian casualties. “We should be looking at whether or not we believe that either the Saudis are doing this purposefully or through negligence,” he said in October. He added, “I’m not sure that either side has proved its case.”

Mr. Pomper said State Department officials tried to counsel Saudi pilots on ways to minimize civilian casualties, mostly without success. But even that effort ignored the larger issue.

“We were in Yemen,” Mr. Pomper said. “We shouldn’t have been there.”

Michael LaForgia is an investigative reporter who previously worked for The Tampa Bay Times and The Palm Beach Post. While in Florida, he twice won the Pulitzer Prize for local reporting. @laforgia_

Walt Bogdanich joined The Times in January 2001 as investigative editor for the Business and Finance Desk. Since 2003, he has worked as an investigative reporter. He has won three Pulitzer Prizes.

Finding US Fingerprints in the Bomb Sites of Yemen

Based in Sana, researchers at Mwatana for Human Rights are documenting deadly attacks on civilians and tracing weapons back to US defense firms, including Raytheon.

Al-Matmah District, Jawf Province

DATE Sept. 20, 2016: DEATHS 15

After a coalition bomb ripped through a truck carrying 15 women and children outside Sana, a Mwatana researcher discovered a shard with Raytheon’s identification number. The resulting report linked the company to the attack and raised doubts about a Saudi internal investigation that said the strike had targeted Houthi rebel commanders. “We document, and we publish,” said Mwatana’s co-founder, Radhya Almutawakel. “This is the work we do.”

Photos: Part of a Raytheon-made GBU-12 bomb that struck a vehicle packed with women and children. Remnants of the civilian truck after the airstrike. Mwatana for Human Rights

Al-Dhihar District, Ibb Province

DATE Sept. 24, 2016: DEATHS 6

Mwatana researchers have chronicled hundreds of strikes, gathering stories of victims and survivors. “Her legs were shredded, and her body was burnt,” one witness said of an 11-year-old girl after a strike on an apartment building. “I gathered her in a blanket. Then I went to look for the rest of the family.”

Photos: A piece from another Raytheon-made GBU-12 bomb, which killed members of the Al-Juma’i family. A bloodied shirt believed to have belonged to a 3- or 4-year-old child killed in the attack. Mwatana for Human Rights

Dar Saad District, Aden Province

DATE April 30, 2015: DEATHS 1

Mwatana’s work has helped shape discussions in the United Nations Security Council as well as in Congress, where Ms. Almutawakel testified last year. “Some of these attacks are likely war crimes,” she told the Foreign Affairs Committee at the US House of Representatives. “Many of them used American-made bombs and munitions. Every single one of these attacks destroyed innocent lives.”

Photos: A shard from a Raytheon-made GBU-12 that killed a woman named Haifa Zawqari and injured others. The residential neighborhood after the strike. Mwatana for Human Rights

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.