South Sudanese Military Leaders’ Wealth, Explained

(May 2020) — Summary: “Making a Killing,” the Sentry’s latest investigative report in its Taking of South Sudan series, raises numerous red flags for corruption and money laundering at the top echelons of military and armed opposition leadership. The report details the unexplained wealth, corporate holdings, and connections to violence of army chiefs of staff Gabriel Jok Riak, James Hoth Mai, Paul Malong Awan, and Oyay Deng Ajak.

According to documents reviewed by The Sentry, each one of these military leaders has moved unexplained wealth through international banks and purchased luxury real estate abroad valued at far more than their modest public servant salaries would allow. Not one has faced domestic

legal accountability for his military or personal conduct, though some have been sanctioned or have had assets seized by foreign governments.

The report also profiles four top-ranking military leaders who commanded troops conducting mass killings in Juba in December 2013—Salva Mathok Gengdit, Bol Akot Bol, Garang Mabil, and Marial Chanuong—as well as Gathoth Gatkuoth Hothnyang, Johnson Olony, and David Yau Yau, militia and opposition leaders involved in major instances of violence both before and during the civil war.

Many of their business interests overlap with one another and with other government officials, as well as with international investors. Some have close personal or business ties to Salva Kiir and his broader network. Their posts have provided easy access to government funds that, in some instances, appear to have financed luxurious lifestyles for relatives overseas, rather than desperately needed infrastructure, economic development, education, or healthcare at home.

The formation of a power-sharing government in February 2020 provides a key opportunity for improved transparency and accountability, but corruption at the highest levels remains a threat to peace and stability. Without major reforms aimed at dismantling the country’s kleptocratic structure, peace will remain fragile.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

- The international community should continue to apply network sanctions, anti-money laundering measures, asset seizure and recovery, and domestic and international investigations to stem the flow of the proceeds of corruption out of South Sudan, provide accountability, and promote peace.

- The SPLA Act of 2009 should be amended to include guidance on procurement processes and independent and empowered oversight bodies within the Ministry of Defense and in the National Legislative Assembly.

- The transitional government should establish and empower a hybrid anti-corruption commission to prosecute the crimes committed during the course of the civil war, as stipulated by the peace agreement; this court should also be able to prosecute economic crimes.

Read the report: https://thesentry.org/reports/taking-south-sudan/

The Taking of South Sudan

A recording of The Sentry’s press conference launching “The Taking of South Sudan,” September 19, 2019.

The Tycoons, Brokers, and Multinational Corporations Complicit in Hijacking the World’s Newest Nation

Overview

The Sentry’s investigation exposes an array of international actors who stand to profit from the US, UK, Asia and elsewhere, the looting of state assets, and reveals one of the biggest companies in the world providing direct support to deadly militias. Our report details the carving up for private profit of the most lucrative economic and government sectors in the world’s youngest nation. Meanwhile, the South Sudanese people starved, were killed, and were run off their homelands.

Executive Summary

The men who liberated South Sudan proceeded to hijack the country’s fledgling governing institutions, loot its resources, and launched a war in 2013 that has cost hundreds of thousands of lives and displaced millions of people.

This report is part of The Taking of South Sudan series. Explore the full series here.

They did not act alone. The South Sudanese politicians and military officials ravaging the world’s newest nation received essential support from individuals and corporations from across the world who have reaped profits from those dealings. Nearly every instance of confirmed or alleged corruption or financial crime in South Sudan examined by The Sentry has involved links to an international corporation, a multinational bank, a foreign government or high-end real estate abroad. This report examines several illustrative examples of international actors linked to violence and grand corruption in order to demonstrate the extent to which external actors have been complicit in the taking of South Sudan.

The local kleptocrats and their international partners — from Chinese-Malaysian oil giants and British tycoons to networks of traders from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya and Uganda — have accumulated billions of dollars. The country’s natural resources have been plundered, lethal militia and military units responsible for atrocities have received financing and kleptocrats have lined their pockets with untold billions of dollars allocated by government programs meant to improve the livelihood of some of the poorest, most vulnerable people in the world.

The spoils of this heist are coursing through the international financial system in the form of shell companies, stuffed bank accounts, luxury real estate and comfortable safe havens around the world for the extended families of those involved in violence and corruption.

Leading South Sudanese officials and their international commercial collaborators are responsive to commercial and political incentives. Without specific, focused, and targeted consequences, it is unrealistic to think their conduct will change. Violence and corruption will remain the norm, meaning that the biggest peace spoiler isn’t a person or an armed group; it is the diseased governing system itself.

However, if serious policy tools of financial coercion are aimed at this kleptocratic network, the possibility exists to alter those incentives, which currently favor pillage and plunder, and in turn impact the calculations of the kleptocrats and their international collaborators in the direction of peace and good governance.

This report is organized into three parts. The first section profiles international actors who have provided direct support to South Sudanese perpetrators of violence. The second section profiles international actors who have formed private businesses with top South Sudanese officials responsible for human rights abuses.

The third section profiles international actors who have benefited from major public procurement scandals in South Sudan. The final section provides recommendations about how policy tools of financial coercion can create a measure of accountability as well as provide leverage in support of peace, human rights and good governance.

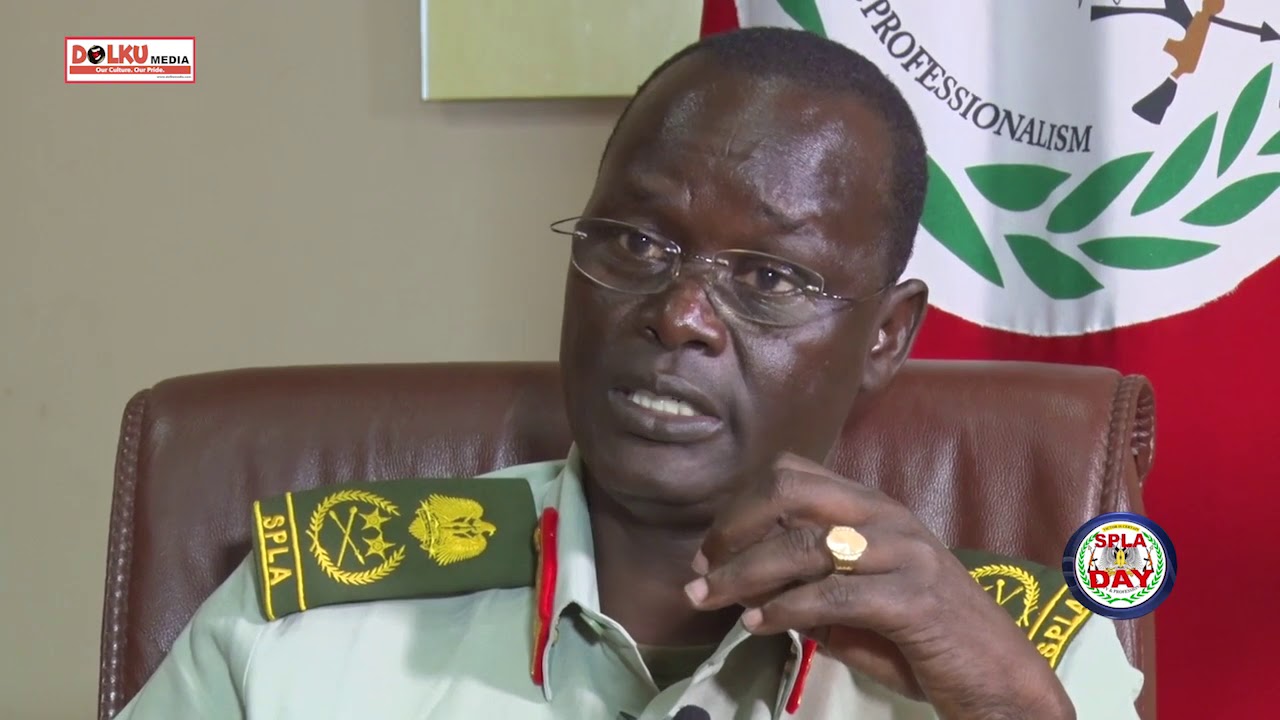

South Sudan Chief of Staff Gabriel Jok Riak.

Making a Killing: South Sudanese Military Leaders’ Wealth, Explained

South Sudan’s last four army chiefs of staff, four high-ranking military leaders, and three opposition militia leaders have engaged in business activities indicative of money laundering and corruption, The Sentry has found. Many of these men share personal or commercial ties with President Salva Kiir, who regularly intervenes in legal proceedings targeting his staunchest friends and allies. All but two have led troops who committed grave human rights violations, starting with the December 2013 mass atrocities in Juba that launched a long and bloody civil war.

This report examines the commercial and financial activities of former Army chiefs of staff Gabriel Jok Riak, James Hoth Mai, Paul Malong Awan, and Oyay Deng Ajak, along with senior military officers Salva Mathok Gengdit, Bol Akot Bol, Garang Mabil, and Marial Chanuong. Militia leaders linked to major instances of violence both before and during the civil war that ended in February 2020 — Gathoth Gatkuoth Hothnyang, Johnson Olony, and David Yau Yau — are also profiled here.

Except for Hoth Mai and Ajak, these men have committed egregious human rights violations with near total impunity since the country’s independence, according to the United Nations and the African Union. Each of these military figures has corporate holdings in South Sudan with possible conflicts of interest, connections to the international financial system, or indicators of corruption and money laundering.

Most secured top government posts after commanding troops who committed major abuses, and some have been shareholders in corporations publicly linked to corruption scandals. General Johnson Juma Okot replaced Jok Riak as chief of staff on May 11, 2020. Okot has also led troops who committed mass violence against civilians, including sexual and gender-based crimes. In addition, he has reportedly been involved in various corruption schemes, such as misappropriating money intended to fund food rations for his troops, leaving them to loot as a means to sustain themselves.

These individuals profited from South Sudan’s corrupt system of patronage both before and after leading forces who committed mass atrocities. Documents reviewed by The Sentry indicate that they exploited their positions of power to empty the state’s coffers and weaken its institutions with little accountability for this corruption or for the human rights violations they perpetrated.

Their posts provided easy access to government funds that appear to have financed luxurious lifestyles for relatives overseas in some instances, instead of desperately needed infrastructure, economic development, education, and health services at home. Critics of this system have been harassed, intimidated, imprisoned, and even killed.

Key Findings

- The four living ex-chiefs of staff, along with Mathok and Chanuong, accumulated significant wealth that well exceeded the scope of their government salaries around that time through commercial and/or corrupt activities.

- The senior military leaders’ business interests overlap with each other, with those of other leading government officials, and with numerous international investors. Many have close business ties to Kiir’s family.

- Nearly every case examined here features significant international connections in the form of foreign business partners, funds transiting through international banks, property purchased abroad, and/or immediate relatives — many holding shares in the same companies — living outside South Sudan. International shareholders come from such diverse countries as China, Kenya, South Africa, Uganda, and the United Kingdom.

- The companies of some current and former security sector leaders received major state contracts or preferential access to foreign currency, among other apparent conflicts of interest. Such conduct constitutes a threat to peace, stability, and transparency.

- The Sentry identified conduct indicative of corruption, financial crimes, and money laundering.

Analysis

The formation of a power-sharing government in February 2020 marks a significant step in the peace process. However, South Sudan still faces a long road to becoming a stable, prosperous country. Without vastly improved and enforced transparency and accountability, the system will remain largely unchanged, the civil war will reignite, and the fledgling peace process will struggle to succeed.

- Limited transparency enables suspicious conduct. While the constitution requires “constitutional office holders” to declare their assets, it fails to mandate public disclosure or to precisely define the term itself. No independent mechanism verifies the veracity and frequency of asset declarations.

In addition, the Public Procurement and Disposal of Assets Act of 2018, which applies to defense and national security institutions, guarantees open bidding. Despite this provision and other similar legislation, defense procurement processes remain murky in practice. The current legislation provides little clarity on how to enforce legally mandated transparency measures in the bidding process, thereby facilitating corruption and conflicts of interest.

- Lack of oversight shields corruption. Defense and security institutions routinely withhold crucial information about their budgets. Alternative mechanisms allow these institutions’ spending to take place outside of the normal budget or auditing process out of concern for “national security.” Major oversight institutions charged with regulating the military are either compromised or toothless, and defense institutions often fail to comply with requests from auditors and investigators, including the auditor general and the Anti-Corruption Commission.

- Violators hold power. Top military leaders under sanctions for corruption, human rights violations, and peace process disruptions have recently held key posts, such as the army’s inspector general and head of procurement. Military institutions have failed to hold their members legally accountable for grave human rights violations or corruption.

A Path Forward

The following measures, if implemented, would hold corrupt military leaders accountable and help South Sudan seize the opportunity presented by the newly formed transitional government to emerge from kleptocracy:

- Tools of financial pressure. The international community — especially the African Union, European Union, United Nations, United Kingdom, and United States—should sustain network sanctions, improve anti-money laundering measures and asset seizure and recovery efforts, and increase domestic and international investigations to stem the flow of the proceeds of corruption out of South Sudan. Financial pressure strategies must provide accountability, promote the peace process, and disrupt spoiler activity.

- Corruption-sensitive security sector reform, oversight, and transparency. Anti-corruption measures must be at the heart of any security reform program that hopes to incentivize peace in South Sudan. Increased oversight and transparency around officials’ asset declarations and military procurement processes, as well as the inclusion of independent auditors, inspectors general, and ethics units in each branch of the military, could reduce corruption that fuels violence. Legislative oversight bodies must be independent and empowered.

- The SPLA Act of 2009 should be amended to include guidance on procurement processes, independent oversight within the Ministry of Defense, and National Legislature oversight. In accordance with the constitution, no militias should exist outside of official structures. Oversight, competitive bidding processes, and enforcement of the rule of law are required to dismantle the system of corruption and impunity that exists within military and para-military structures.

- Accountability and the peace process. The transitional government should establish and empower a hybrid anti-corruption commission to prosecute crimes committed during the civil war, as stipulated by the peace agreement. If the government fails to establish the commission, the international community should exert pressure and help stand up a hybrid court to hold perpetrators accountable for gross human rights violations and economic crimes.

Download the full report.

Explore the Series

- “Al-Cardinal: South Sudan’s Original Oligarch” [October 7, 2019]

- “Untapped and Unprepared: Dirty Deals Threaten South Sudan’s Mining Sector” [April 2, 2020]

- “Making A Killing: South Sudanese Military Leaders’ Wealth, Explained” [May 27, 2020]

The Sentry is an investigative and policy team that follows the dirty money connected to African war criminals and transnational war profiteers and seeks to shut those benefiting from violence out of the international financial system. By disrupting the cost-benefit calculations of those who hijack governments for self-enrichment in East and Central Africa, the deadliest war zone globally since World War II, we seek to counter the main drivers of conflict and create new leverage for peace, human rights, and good governance.

The Sentry is composed of financial investigators, international human rights lawyers, and regional experts, as well as former law enforcement agents, intelligence officers, policymakers, investigative journalists, and banking professionals. Co-founded by George Clooney and John Prendergast, The Sentry is a flagship initiative and strategic partner of the Clooney Foundation for Justice.

© Copyright 2020 The Sentry, All Rights Reserved. Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.