The US Nuclear Presence in Western Europe, 1954-1962

The National Security Archive

• Germans and Italians Did Not Seek Formal Agreement to US Nuclear Weapons Storage on Their Territory

• Declassified Records Reflect Debates over Nuclear Weapons Stockpile, Use Decisions, and Independent Nuclear Capabilities

• New Document Shows French Concern that US Might Not Use Nuclear Weapons in a Crisis

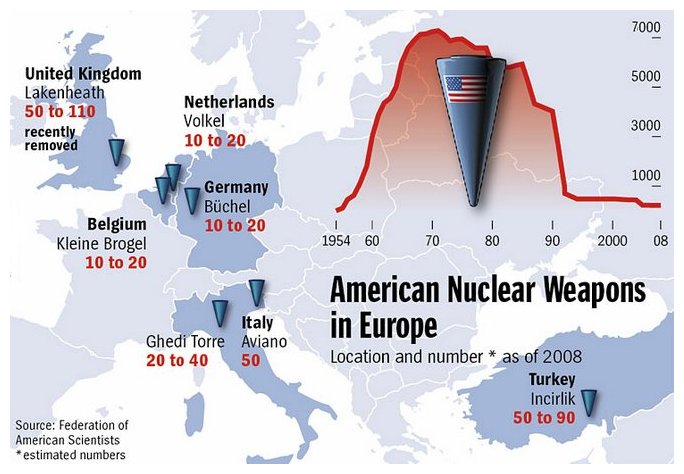

• Nukes in Europe Peaked in 1960s at 8,000; over 100 Remain Today, and Are Still Controversial

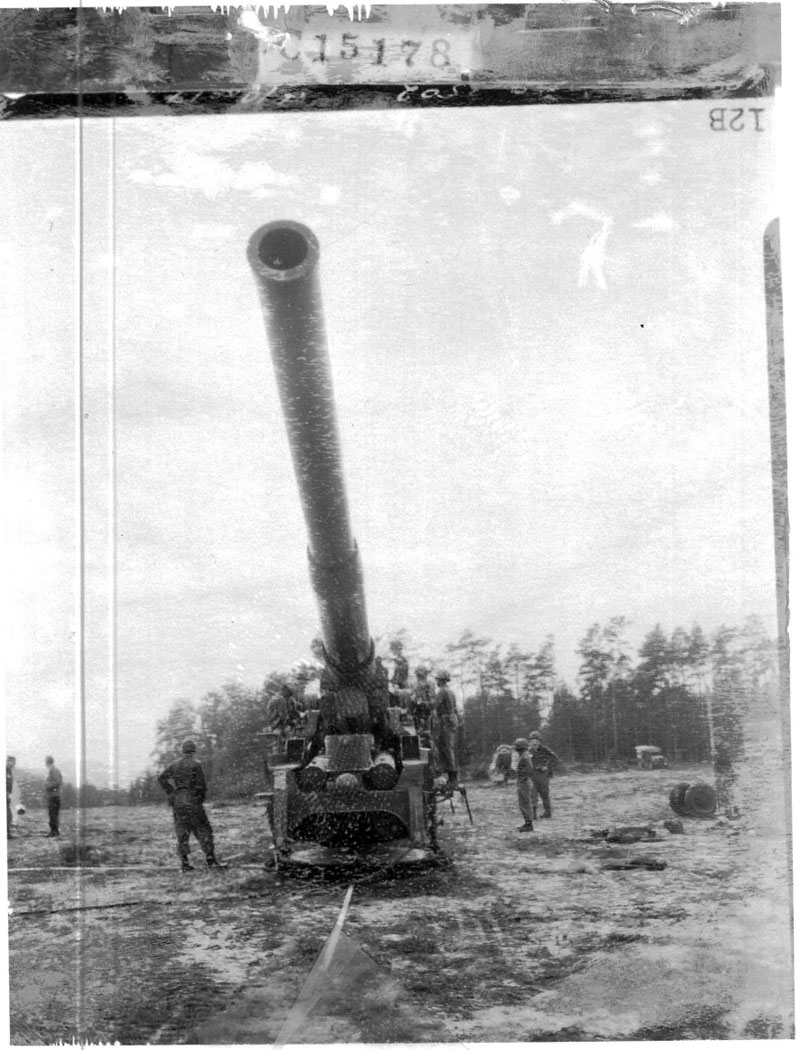

A 280 mm. nuclear-capable cannon being set up for test firing by the 39th Field Artillery Battalion at the Grafenwohr Training Area, West Germany, 28 September 1958. The M65 cannon could fire the W9 nuclear warhead, which had an explosive yield of some 15 kilotons. A gun-type atomic weapon, it was the same kind of warhead that was used to destroy Hiroshima. (National Archives Still Picture Division, Record Group 111-CS, box 31)

WASHINGTON, DC (July 21, 2020) — Recent debates over US nuclear weapons in Western Europe make it worth looking at how those forces got there in the first place.

In the 1950s, when fear of Soviet military power was at its height, NATO allies like West Germany and Italy were remarkably compliant to US wishes regarding the storage of nuclear armaments on their soil — and ultimately their potential use in a European war — according to newly released State Department and Defense Department records posted today by the nongovernmental National Security Archive. The governments in Bonn and Rome made no objections when Washington came calling and did not even pose questions about when or how the weapons might be used.

Other governments, notably France, did raise concerns but sometimes very different ones. In one important new document reporting on a sensitive North Atlantic Council meeting from October 1960, the Greeks wondered whether the Americans would consult with their allies before resorting to nuclear war, while the French, who wanted their own force de frappe, told the group their worry was Washington might not use their weapons at all in a crisis.

Today’s posting provides a significant window into the delicate issues surrounding the creation and management of the nuclear stockpile in Europe. Much about this topic is still classified. Along with allied perspectives, the documents describe inter-agency disputes between State and Defense over issues such as whether to grant certain allies custody over the weapons.

President Dwight Eisenhower did not oppose sharing possession of nuclear capabilities — in order to strengthen NATO and reduce dependence on the US — but he also insisted that the US should have full freedom to deploy its arsenal at will. Current public debates in Europe show that the stationing of nuclear weapons is still highly controversial, even though the number of US bombs on the continent has dropped from more than 8,000 to between 100-150 since the end of the Cold War.

The US Nuclear Presence in Western Europe, 1954-1962

by William Burr

From MC-48 to the Atomic Stockpile System, 1954-1960

Since the mid-1950s, during the Dwight D. Eisenhower presidency, the US military has stored nuclear weapons at military bases on the territory of its European NATO allies for use in the event of conflict with the Soviet Union or the Russian Federation. At the time, State Department officials believed that as long as the US was seeking to store nuclear weapons in Europe and to obtain “the use rights which we require,” it “must be prepared to pay some price.”

Part of the price that Washington decided to pay was to develop arrangements that have been in place for decades: training NATO allies to use nuclear weapons delivery systems and making available nuclear weapons for use by alliance forces in the event of war.

In emergency conditions, the US CINCEUR [Commander in Chief European Command] could order the immediate use of the weapons by NATO. In other circumstances, use of the weapons required the consent of NATO’s top policymaking body, the North Atlantic Council. But the US president had a controlling voice in decisions to use American nuclear weapons. Thus, President Eisenhower’s “emergency actions pouch” (later known as the “football”) would include a directive authorizing the transfer of nuclear weapons to NATO forces.

The deployments were consistent with policy priorities established in late 1954 by NATO Military Committee document 48, which mandated nuclear weapons use in conflict with the Soviet Union, including a Soviet conventional attack on Western Europe. But NATO’s endorsement of MC 48 did not mean widespread acceptance of its ideas in Western Europe. According to Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) General Alfred Gruenther, it would take time before Europeans saw the bomb as a “conventional means and they stop being afraid of it.”

Much about the US-NATO nuclear enterprise has been secret since its inception. The numbers of US nuclear weapons deployed and their locations in NATO Europe was classified secret during the Cold War and has remained so (for example, in 2018 the Netherlands Council of State, with US support, rejected an appeal for information on US nuclear weapons in that country).

The current numbers of nuclear bombs and their locations is an official secret, although it is widely understood that about 100 to 150 bombs are kept at air bases in Belgium, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and Turkey.[1] Before the early 1990s, however, the US had thousands of nuclear weapons in NATO Europe, with the late 1960s a peak in the range of 8,000, but when the Cold War ended the US drastically cut back on the deployments,

Controversy has surrounded the nuclear deployments for years, especially in Germany and a debate has resumed there, begun mainly by Greens and Social Democrats, over whether that country should spend large sums on modernizing its nuclear-capable military aircraft or whether nuclear weapons should even be based in Germany. In the United States an attempt is being made to initiate a broader debate over whether forward-based nuclear weapons are essential to the integrity of NATO and the deterrence of Russia.[2]

To provide perspective on the long-term — if now attenuated — US nuclear presence in NATO Europe, the National Security Archive publishes today a special collection of declassified documents on the early years of US nuclear deployments on the continent in the context of alliance nuclear policy and nuclear use consultation arrangements. Central to the posting are documents on the creation of the stockpile arrangements by which nuclear weapons would be made available to trained units of NATO countries in the event of an East-West conflict.

Other documents illuminate the NATO strategy which provided the context for the stockpile system and the problem of nuclear use authority raised by US control over nuclear weapons deployed to NATO countries.

Some of the documents in today’s posting were published previously by the National Security Archive in various compilations distributed on the Digital National Security Archive (DNSA) subscription service, including the Berlin Crisis, 1958-1962, US Nuclear History, 1955-1968, and Nuclear Nonproliferation, 1955-1968. Other documents are published on-line for the first time, including a number of items obtained from the US National Archives.

The Nuclear Alliance

With the nuclear-armed United States a leading member and a guarantor of European security, NATO was a nuclear alliance from the beginning, but nuclearization accelerated in the mid-1950s. Key developments were the deployment of nuclear weapons to West Germany and Italy, documented in this collection, but also the acceptance of Military Committee 48 which made nuclear weapons central to alliance defense and deterrence strategy.

With the US’s central role in NATO, however, President Eisenhower assumed that any nuclear use in an East-West war in Europe would depend on a decision from Washington: the “US must retain freedom to use atomic weapons on its own decision in the event of threat to our own forces.” [3]

Putting nuclear weapons at the heart of alliance strategy left the European allies in a difficult position because they had no access to the weapons. To solve that political and diplomatic problem, State Department officials supported training NATO forces in the use of nuclear weapons and making arrangements to provide them with such weapons in the event of war, with the US retaining custody of them otherwise.

This was consistent with Eisenhower’s policy preferences, which were that European allies needed nuclear capabilities to reduce their dependence on the United States. While the Defense Department would propose turning over custody of the weapons to allies such as France, the AEC and the State Department rejected that option as potentially destabilizing and inconsistent with nonproliferation policy.[4]

Declassified documents posted today chart the negotiation of the bilateral agreements that established the stockpile system. Each participating country, which included West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Turkey, among others, signed an agreement covering the introduction of US custodial and training personnel and financial costs. Creation of the stockpile system also required agreements covering special arrangements for the sharing of nuclear weapons information with military units.

Even though French officials had been early proponents of the stockpile, France refused to participate. With its own nuclear weapons program in the works and the highly nationalistic Charles De Gaulle in power, the French leader refused to allow the introduction of nuclear weapons to which another country had legal title, even if they were to be assigned to French forces.

However, Paris and Washington agreed to a plan for French military units in West Germany to participate in the stockpile. As long as the weapons were not on their territory, the French had no objection to a proposal to assign US nuclear weapons to their forces in Germany.[5]

That the West Germans would participate in the nuclear stockpile raised objections by the Soviet bloc, which had not forgotten German aggression only a few years earlier. To assuage those concerns, the United States would assert that it had “exclusive custody” of the weapons [see Part II of this posting, forthcoming] but ownership and legal control of the weapons and authority to order their use was one thing, while the requirements of military readiness were another.

The latter left wide berth for attenuation of US control. As shown in the Defense Department’s history of custody, the US military depended on the host nation for security of stockpile sites. Moreover, the Defense Department permitted storage of weapons on host nation strike aircraft, which would cause great concern when it became known to members of Congress in 1960. As for President Eisenhower, he was more relaxed about custody, believing that a strong NATO required effective nuclear roles for the allies.

So far, the only NATO countries where the US government has acknowledged that it deployed nuclear weapons are Germany and the United Kingdom, but the details remain secret.[6] The record of the stockpile negotiations also remains classified although archival sources on the Italian negotiations are available (to be discussed in more detail in Part II of this posting).

One of the key issues with the US nuclear presence in Western Europe and US guarantees for European security was the matter of consultations over the fateful problem of nuclear weapons use. This became an especially concerning issue within NATO once the Soviets began developing ballistic missiles. Even with the stockpile system in place, the US still had official control of the weapons and members of NATO’s top decision-making body, the North Atlantic Council, wondered whether the US would consult them adequately before making a nuclear use decision.

A never-before-published record of a NAC meeting in October1960 illustrates the range of concerns about US control of nuclear weapons and consultation with allies in a crisis: whether the US would use the bomb without consultation or whether it would use the bomb in a crisis. A French diplomat argued that France “would not fear the US using atomic weapons, but [feared] that the US might not react.” He also declared that France’s “capability to launch atomic weapons would be pressure on the US to do so.”

Part II of this posting will document developing State Department and congressional concerns about nuclear stockpile arrangements, including the extent to which the United States had “exclusive custody” over the weapons. Concerns about the security of the weapons and the risk of unauthorized use led the new Kennedy administration to halt temporarily US nuclear deployments to NATO forces and to press for the development of Permissive Action Links (PALs) to tighten US control of the weapons.

READ THE DOCUMENTS

NOTES

[1]. For a major study, see Hans M. Kristensen, US Nuclear Weapons in Europe A Review of Post-Cold War Policy, Force Levels, and War Planning (Washington, D.C., Natural Resources Defense Council, 2005). For a recent update see Kristensen, US Nuclear Weapons in Europe, Federation of American Scientists, 1 November 2019.

[2]. Jon B. Wolfsthal, “America Should Welcome a Discussion about NATO’s Nuclear Strategy,” The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 29 June 2020.9 June 2020.

[3]. For an invaluable survey of NATO history, see Timothy Andrews Sayle, Enduring Alliance; A History of NATO and the Postwar Global Order (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019).

[4]. For Eisenhower’s thinking, see Marc Trachtenberg, A Constructed Peace: The Making of the European Settlement, 1945-1963 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999).146-156 and elsewhere in the volume.

[5]. Trachtenberg, A Constructed Peace, 223.

[6]. The situation has not changed since the 1999 declassification of a 1978 Pentagon study, History of the Custody and Deployment of Nuclear Weapons: July 1945 through September 1977, which was first discussed in an article by Robert S. Norris, William Arkin, and William Burr, “Where They Were,” The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November-December 1999, 28-35.

[8] For some of the literature on MC-48 and NATO strategy, see Trachtenberg. A Constructed Peace, 158-160; Robert A. Wampler, “Ambiguous Legacy: The United States, Great Britain and the Foundations of NATO Strategy, 1948-1957,” (Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1991), 616-665, and Andreas Wenger, “The Politics of Military Planning: Evolution of NATO’s Strategy,” in Vojtech Mastny, Sven C. Holtsmark, and Andreas Wenger, eds.,War Plans and Alliances in the Cold War: Threat Perceptions in the East and West (London: Routledge, 2006), 168-170.

[9]. Robert J. Watson, History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Into the Missile Age, 1956-1960 (Washington, D.C.: Historical Office, Office of the Secretary of Defense, 1997), 516.

[10]. See Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe, SHAPE History 1958, August 1967, 15-31.

[11]. For US nuclear relations with Italy, including a full account of the stockpile negotiations, see Leopoldo Nuti, La sfida nucleare. La politica estera italiana e le armi atomiche, 1945-1991. (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2008).

[12]. Robert J. Watson, Into the Missile Age, 470, 579, and 584

RELATED LINKS

United States Secretly Deployed Nuclear Bombs In 27 Countries and Territories During the Cold War

October 20, 1999

US Nuclear Weapons Deployments in Chichi Jima and Iwo Jima

December 13, 1999

US Government Debated Secret Nuclear Deployments in Iceland

August 15, 2016

NATO’s Original Purpose: Double Containment of the Soviet Union and “Resurgent” Germany

December 11, 2018

Nuclear Weapons and Turkey Since 1959

October 30, 2019

THE NATIONAL SECURITY ARCHIVE is an independent non-governmental research institute and library located at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C. The Archive collects and publishes declassified documents acquired through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). A tax-exempt public charity, the Archive receives no US government funding; its budget is supported by publication royalties and donations from foundations and individuals.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.