Iraq War: Secret Memo Reveals

Bush-Blair Plans to Topple Saddam Hussein

US president told British PM he ‘didn’t care’ who replaced Saddam Hussein as pair plotted PR campaign to sell war a year before invasion

David Hearst / Middle East Eye

(January 13, 2022) — George W Bush told Tony Blair he did not know who would replace Saddam Hussein in Iraq when they toppled him and that he “did not much care”, according to an explosive top secret account of the meeting seen by Middle East Eye.

The former US president was blithe about the consequences of launching an invasion at a crucial meeting with the British prime minister at his Texas ranch in 2002, almost a year before the war was launched.

“He didn’t know who would take Saddam’s place if and when we toppled him. But he didn’t much care. He was working on the assumption that anyone would be an improvement,” the British memo, written by Blair’s top foreign policy adviser at the time, reads.

Bush believed — but the memo says he would not say publicly — that a “moderate secular regime” in post-Saddam Iraq would have a favourable impact both on Saudi Arabia — a close US ally — and Iran.

He had said it was essential to ensure that acting against Saddam would enhance rather than diminish regional stability. Bush “had therefore reassured the Turks that there was no question of the break-up of Iraq and the emergence of a Kurdish state”.

The memo also reveals how as early as April 2002, more than eight months before United Nations weapons inspectors went into Iraq, Blair was aware that they might have to “adjust their approach” should Saddam give them free rein.

This is believed to be the first reference to a strategy, which ended with the creation of the infamous “dodgy dossier” of concocted intelligence making the case for war, key details of which were later admitted to be false.

The memo hardens the central findings of the public inquiry into the war led by John Chilcot which concluded in 2016 that the UK chose to join the invasion before peaceful options had been explored, that Blair deliberately exaggerated the threat posed by Saddam, and that Bush ignored advice on post-war planning.

It was written by David Manning, Blair’s top foreign policy adviser, one day after the meeting at the president’s ranch in Crawford, Texas, on Saturday 6 April 2002.

Apart from Bush and Blair, only a handful of officials were present from both sides, and much of the discussion between the two leaders was conducted one-on-one.

The president and prime minister had developed a particularly close relationship in the aftermath of the 11 September 2001 al-Qaeda attacks in the US, following which Blair had pledged to “stand shoulder to shoulder with our American friends”. The two trusted and confided in each other more than they did some of their own colleagues.

The UK had been a key supporter and participant in the US-led invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001. Iraq, which had long been subject to UN sanctions imposed over Saddam Hussein’s weapons programmes, had also been in US sights since the launch of the so-called “war on terror”.

In another memo sent to Blair weeks before the Crawford meeting, Manning reported that Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s national security adviser, had told him over dinner that Bush really needed Blair’s support and advice, angered as he was at the reaction he was getting in Europe.

‘Exceptionally Sensitive’

At the time, the plan to launch a war was a closely guarded secret even within senior US military circles. Manning notes that only a “very small cell” in US Central Command (Centcom) was involved in drawing up plans, with most high-ranking military officials kept in the dark.

He wrote: “This letter is exceptionally sensitive and the PM instructed it should be very tightly held, it should be shown only to those with a real need to know and no further copies should be made.”

The memo was addressed to Simon McDonald, foreign secretary Jack Straw’s principal private secretary, and circulated to a handful of other senior British officials.

They were Jonathan Powell, Blair’s chief of staff; Michael Boyce, the chief of defence staff; Peter Watkins, the principal private secretary to defence minister Geoff Hoon; Christopher Meyer, the British ambassador in Washington; and Michael Jay, the permanent secretary at the foreign office.

Rice told the Crawford ranch meeting that “99 percent” of Centcom was unaware of the Iraq war plans.

Manning recounts how Bush and Blair war gamed the issue of sending weapons inspectors into Iraq.

Both leaders were concerned about the level of European opposition to military action and the memo notes that Bush accepted that “we need to manage the PR aspect of all this with great care”.

Manning wrote: “The PM said we needed an accompanying PR strategy that highlighted the risks of Saddam’s WMD programme and his appalling human rights record. Bush strongly agreed.”

“The PM would emphasise to European partners that Saddam was being given an opportunity to co-operate. If, as he expected, Saddam failed to do so, the Europeans would find it very much harder to resist the logic that we must take action to deal with an evil regime that threatens us with its WMD programme.”

Blair was concerned then by the possibility that Saddam would let UN inspectors in and allow them to go about their business — which in fact subsequently happened.

Inspectors returned to the country in November 2002 and remained there until 18 March 2003, one day before the launch of the US-led attack on Iraq.

In February 2003, Hans Blix, the UN’s chief inspector, told the Security Council that Iraq appeared to be cooperating with inspections, and said that no weapons of mass destruction had been found.

Blair told Manning after a private conversation with the US president: “Bush had acknowledged that there was just a possibility that Saddam would allow them in and go about their own business. If that happened we would have to adjust our approach accordingly.”

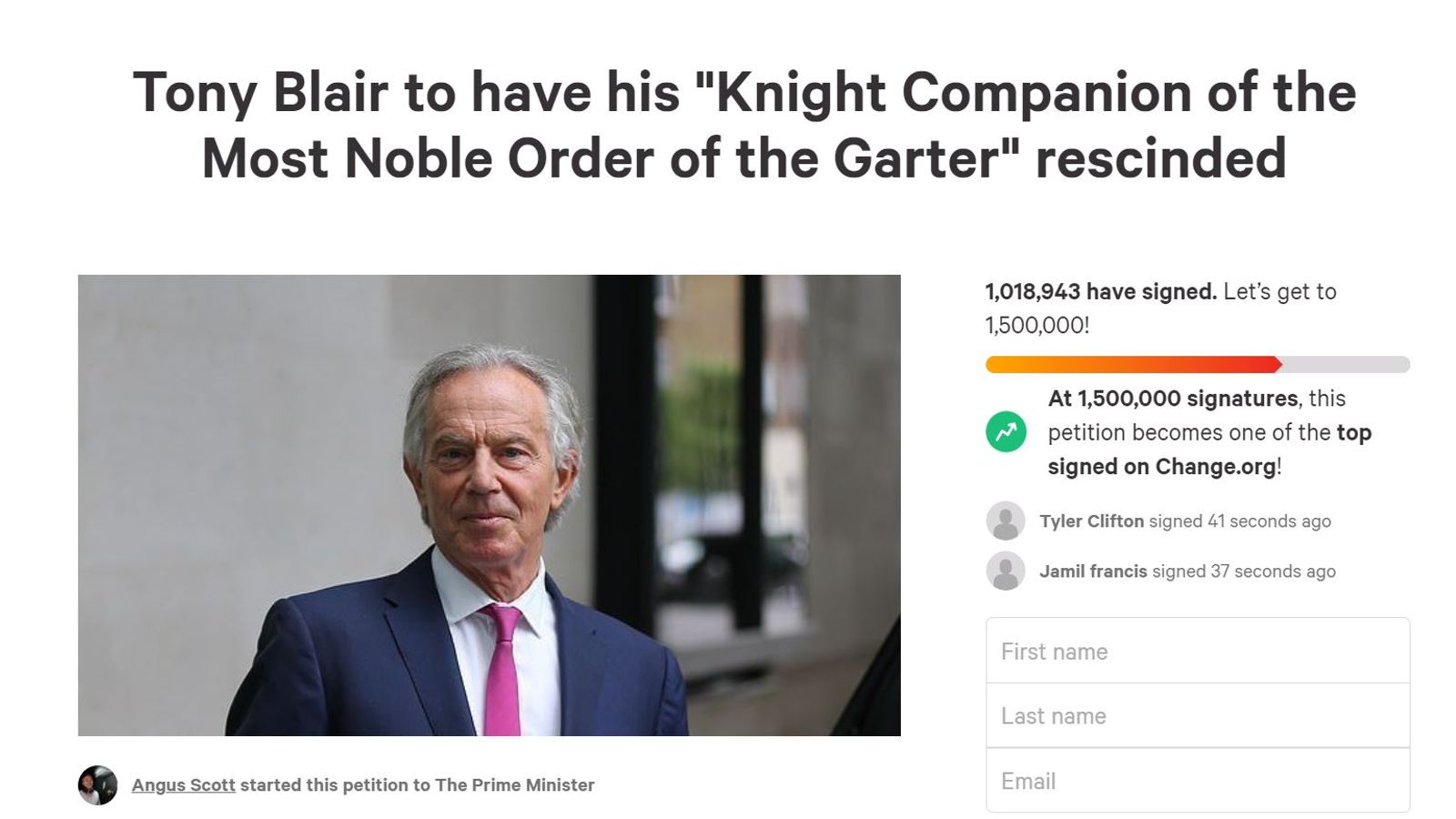

Furore over Knighthood

The Manning memo was first leaked to the Daily Mail, amid the public furore over the award of a knighthood to Blair. Middle East Eye has been passed a copy of the text of the memo, which it is publishing in full.

A petition to have Blair’s knighthood rescinded has since gathered more than one million signatures.

The memo is the second written by Manning on Iraq to see the light of day. In 2004, the Daily Telegraph newspaper published details of a memo by the British diplomat to Blair concerning preparations for the Crawford summit.

Dated 13 March 2002, Manning tells Blair of his dinner with Rice and their conclusion that failure “was not an option”.

Manning writes: “It is clear that Bush is grateful for your support and has registered that you are getting flak. I said that you would not budge in your support for regime change but you had to manage a press, a parliament and a public opinion that was very different than anything in the States. And you would not budge either in your insistence that, if we pursued regime change, it must be very carefully done and produce the right result. Failure was not an option.”

Manning told Blair that the issue of weapons inspections “must be handled in a way that would persuade European and wider opinion that the US was conscious of the… insistence of many countries for a legal basis.”

On the visit itself, Blair was told that Bush would want to pick his brains. “He also wants your support. He is still smarting from the comments by other European leaders on his Iraq policy.”

Blair received a number of warnings from top advisers just before the summit. Peter Ricketts, the British government’s national security adviser, wrote to Blair that scrambling to establish a link between Iraq and al-Qaeda was “so far frankly unconvincing”.

Even if they successfully made the case that the threat posed by Iraq ought to be taken seriously because of the country’s use of chemical weapons in its 1980s war against Iran, “we are still left with a problem of bringing public opinion to accept the imminence of a threat from Iraq. This is something the prime minister and president need to have a frank discussion about”.

Straw, then foreign secretary, wrote to Blair on 25 March 2002 that the rewards of Crawford would be few and the risks high.

He warned of “two legal elephant traps”. Straw wrote that regime change in Iraq per se was no justification for military action, noting “it could form part of the method of any strategy, but not a goal”.

The second was whether any military action would require a fresh mandate from the UN Security Council.

“The US are likely to oppose any idea of a fresh mandate. On the other side, the weight of legal advice here is that a fresh mandate may well be required,” Straw wrote.

“Whilst that is very unlikely, given the US’s position, a draft resolution against military action with 13 in favour (or handsitting) and two vetoes against could play very badly here.”

Blair’s Foreign policy advisor David Manning.

‘Closest to the Horse’s Mouth’

The Manning memo did surface during the Iraq inquiry, but was never published and only obliquely referred to by Roderic Lyne, a member of the inquiry panel, when Manning gave evidence in 2010.

Addressing Manning, Lyne said: “You were obviously the closest person to the horse’s mouth on this one.”

Lyne went on to ask Manning whether Crawford was a decision point for Blair. Manning replied that he thought at Crawford that US thinking had “gone up a gear”.

Bush had created a team and asked them to give him options and a British official was later invited to Centcom’s headquarters in Tampa, Florida, to see what those options were, he said.

When contacted for comment, a spokesperson for Manning told MEE: “Sir David would like to reiterate that in all correspondence relating to this period he has nothing to add to the evidence he gave to the Chilcot Inquiry.”

MEE has also approached Bush and Blair for comment.

How Bush and Blair Plotted War in Iraq:

Read the Secret Memo in Full

Editor’s note: In April 2002, Tony Blair, the British prime minister, visited US President George W. Bush at his ranch in Crawford, Texas.

The weekend meeting has long been identified as a key moment in the buildup to the US-led invasion of Iraq in March 2003, but details of what was discussed between the pair have remained a matter of speculation.

Middle East Eye has seen a copy of a secret memo about the meeting written by David Manning, Blair’s chief foreign policy adviser, who accompanied him to Crawford.

It was sent to Simon McDonald, principal private secretary to foreign secretary Jack Straw, and shared with five other senior British officials: Jonathan Powell, Blair’s chief of staff; Mike Boyce, chief of defence staff; Peter Watkins, principal private secretary to defence secretary Geoff Hoon; Christopher Meyer, UK ambassador to the US; and Michael Jay, permanent secretary at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

The text of that memo is published below for the first time.

Subject: Prime Minister’s visit to the US April 5 -7 2002.

Sent: April 8, 2002

From: David Manning

To: Simon McDonald

CC’d: Jonathan Powell, Sir Mike Boyce, Peter Watkins, Christopher Meyer, Sir Michael Jay

The Prime Minister and Mrs Blair were the guests of President and Mrs Bush at Crawford, Texas, from April 5 -7.

Much of the [Blair-Bush] discussions were tete a tete. However, Jonathan Powell and I joined the President and the PM at Crawford ranch for informal talks on the morning of Saturday April 6.

Condi Rice [Bush’s national security advisor] and Andy Card [Bush’s chief of staff] accompanied Bush.

Among the issues discussed was Iraq and other topics separately.

This letter is exceptionally sensitive and the PM instructed it should be very tightly held, it should be shown only to those with a real need to know and no further copies should be made.

Bush said he and the PM had discussed Iraq on their own over dinner the previous evening.

At present Centcom had no war plan as such. Thinking ahead so far was on a broad and central level, though a very small Centcom cell had recently been established in conditions of great secrecy to look at the detailed military planning.

Condi Rice said 99 per cent of Centcom were unaware of this.

When it had done more work Bush would be ready to agree to UK and US planners sitting down together to examine the options. He wanted us to work through the issues together. Whatever plan emerged we had to ensure victory. We could not afford to fail.

But it would be essential to ensure that acting against Saddam enhanced rather than diminished regional stability. He had therefore reassured the Turks that there was no question of the break-up of Iraq and the emergence of a Kurdish state.

But there were nevertheless a number of imponderables.

He didn’t know who would take Saddam’s place if and when we toppled him.

But he didn’t much care. He was working on the assumption that anyone would be an improvement.

Nevertheless Bush accepted we needed to manage the PR aspect of all this with great care.

He accepted we needed to put Saddam on the spot over the UN inspectors, we should tell him that we wanted proof of his claim that he was not developing WMDs. This could only be forthcoming if UN inspectors were allowed in on the basis that they could go anywhere inside Iraq at any time.

Bush added that Saddam could not be allowed to have any say over the nationality or composition of the inspection team.

He said the timing of any action against Saddam would be very important. He would not want to launch any operation before the US Congressional elections in the autumn. Otherwise he would be accused of warmongering for electoral benefit.

In effect this meant there was a window of opportunity between the beginning of November and the end of February.

‘Although we may not decide to do it this year at all.’

The PM said no one could doubt the world would be a better place if there were regime change in Iraq. But in going down the inspectors route, we would have to give careful thought to how we framed the ultimatum to Saddam to allow them to do their job.

Saddam would very probably try to obstruct the inspectors and play for time. This was why it was so important we insisted they must be allowed in at any time and be free to visit any place or installation.

The PM said we needed an accompanying PR strategy that highlighted the risks of Saddam’s WMD programme and his appalling human rights record. Bush strongly agreed.

The PM said this approach would be important in managing European public opinion and in helping the President construct an international coalition.

The PM would emphasise to European partners that Saddam was being given an opportunity to co-operate.

If, as he expected, Saddam failed to do so, the Europeans would find it very much harder to resist the logic that we must take action to deal with an evil regime that threatens us with its WMD programme.

We would still face the question of why we had decided to act now, what had changed?

The answer had to be that we must think ahead, this was one of the lessons of 9/11: failure to take action in good time meant the risks would only grow and might force us to take much more costly action later.

The President agreed with Mr Blair’s line of argument.

It was also Bush’s view, though he would not be saying this publicly, that if a moderate secular regime succeeded Saddam in Iraq this would have a favourable impact on the region particularly on Saudi Arabia and Iraq.

Comment:

The PM later commented to me privately that he had spoken again to Bush about the issue of UN inspectors. Bush had acknowledged that there was just a possibility that Saddam would allow them in and go about their own business. If that happened we would have to adjust our approach accordingly.

Meanwhile it was worth ramping up the pressure on Saddam and making it plain that if he didn’t accept the inspectors we reserved the right to go in and deal with him.

The PM also told me that Bush had been clear that he wanted to build a broad coalition for his Iraq policy. This had apparently persuaded him to dismiss those on the American Right who were arguing there was no need and no point in bothering with UN inspectors.

George Bush senior may have been influential on this point. Bush told the PM separately that the US must construct a coalition for dealing with Iraq whatever ‘Right wing kooks’ might be saying.

It is clear from these exchanges that military planning is not yet advanced very far. Only when more progress is made will Bush be ready to allow our own planners to discuss the options with Centcom. It also seems clear that Bush has still not finally decided that military action will be feasible at the end of this year, even if he has provisionally earmarked the November-February period for a possible campaign.

Recommended

• Tony Blair can never escape his role in the Iraq disaster

• Tony Blair’s knighthood sparks petition calling for its withdrawal

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.