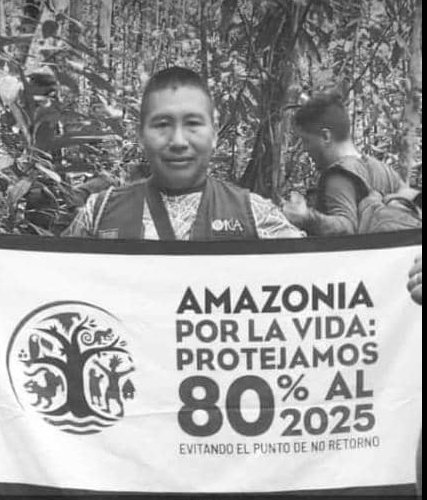

Indigenous Leader Virgilio Trujillo Arana:

Shot in the Head Three Times

The Guardian UK

PUERTO ORDAZ (July 2, 2022) — A Venezuelan indigenous leader who was an opponent of armed groups and illegal mining has been shot dead in the Amazonas state capital, a non-governmental organization and three people with knowledge of the case said.

Virgilio Trujillo Arana, a 38-year-old indigenous Uwottuja man, was a defender of the Venezuelan Amazon and had set up community groups to act as guardians of the Autana municipality of Amazonas.

Arana was shot in the head three times by a gunman who fled to a waiting vehicle in Thursday’s attack in the city of Puerto Ayacucho. He had reportedly received threats relating to his work.

“In life, Trujillo Arana strongly opposed the presence of foreign groups and illegal mining exploitation in the indigenous territories of the Uwottuja people, in the Alto Guayapo area,” indigenous rights NGO AC Kape Kape wrote on Twitter.

The Uwottuja community is made up of about 15,000 people.

Non-governmental organizations and a United Nations report have denounced the presence of violent criminal groups that control gold mines in the jungle.

The ministry of communication and information and the prosecutor’s office did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Communities from the town of Uwottuja announced last February their decision to defend their territory against a “silent invasion” by criminal groups, rejecting illegal mining exploitation as well as the use of their land for illicit activities.

Mining has been prohibited since 1989 in Venezuela’s southern Amazonas state, which is not part of the so-called Arco Minero, or Mining Arc, a gold exploitation zone 111,000 sq km created by decree in 2016 by the government of President Nicolas Maduro.

The office of United Nations high commissioner for human rights Michelle Bachelet has asked the government to regularize mining activities and guarantee that they are carried out under international and environmental standards.

Looking for gold at the La Culebra gold mine. P(hoto: Juan Barreto/AFP)

Gold Fever Fuels Gangs and Insecurity:

‘There Will Be Anarchy’

Emma Graham-Harrison and Clavel Rangel / The Guardian

PUERTO ORDAZ (June 8, 2019) — Puerto Ordaz was once Venezuela’s industrial hub, a modernist dream of broad boulevards and ranks of factories and gateway to a belt of rich oilfields that funded government largesse for decades.

As the economy has crumbled though, the modern city of steel and aluminium has been swallowed by its past, transformed into little more than an outpost of the gold mines a few hours’ drive away in the fringes of the Amazon.

There, in swampy, malaria-ridden pits controlled by criminal gangs, men labour away much as they would have done centuries ago. The lumps of yellow metal they extract through backbreaking work now power the city; gold has become so pervasive that medieval-style barter is replacing hard currency across the city.

Gold also increasingly pays the bills for the national government in distant Caracas. With oil revenues dwindling and US sanctions biting, the president, Nicolás Maduro, has been relying on wealth from the mines to keep the government afloat during a months-long standoff with the opposition leader, Juan Guaidó.

So the government has allowed the illegal industry and the armed groups that run them to flourish, spawning an epidemic of violence, disease and environmental devastation, and drawing in much of the remaining population of Puerto Ordaz.

“More than half our clients want to pay in gold,” said one estate agent in Puerto Ordaz, who described a recent nerve-racking drive through the increasingly lawless city to broker a deal, following buyers carrying an apartment’s worth of precious metal.

“The client said ‘come in our car’, but I said: ‘No, we are traveling behind you.’ With the insecurity you don’t know who knows you have gold,” added the agent, who is still struggling with the new norms of doing business, and asked not to be named for her safety.

Even the universities have been swept up in the gold rush. “In November, one of the girls who is studying here told me: ‘A degree is not expensive, because its only 2.5g of gold [for a semester],’” said Arturo Peraza, rector of the city’s influential Universidad Católica Andrés Bello.

“It was the first time I learned the value of a university education in grams of gold. I could not have imagined it.”

Shopping malls have been taken over by metal dealers, who sit idly in rows of shops that once sold electronics or clothes, waiting for miners to arrive with crumbs of yellow to exchange for cash. Men with wary eyes and barely concealed guns stand near the main exits.

They are the most discreet public face of an epidemic of violence nurtured in the mines, but already spilling beyond them. Gold fever has fuelled a proliferation of armed gangs, drawn in a Colombian guerrilla group, the ELN, fostered corruption in the national security forces, and insecurity in Puerto Ordaz.

¡Virgilio Trujillo Arana, Presente!

Disease has also festered in the mines then followed gold and miners to Puerto Ordaz, reviving malaria in a region where it was once stamped out.

Troubles in the country’s remote east usually make fewer headlines than crises along the western border with Colombia, the main route for millions of migrants trying to escape Venezuela’s misery. But locals say the lawlessness brewing in the remote mining camps is an underestimated risk.

“Here in Bolívar state, we have the conditions to finance chaos, because we have gold,” said Peraza.

“In Caracas they don’t know what is going on here. They are so focused on the question of oil, because its been the economic heart of the country for 100 years. But the oil has dried up and no one has realised how reality changed.”

Gold is far easier to transport, and less complex to extract, if you have a workforce desperate enough to do the dangerous, dirty work by hand.

The men who dig for gold – and it is all men, women only work as cooks or in brothels at the mines – include professionals whose jobs were engulfed by the crisis or whose salaries have been eroded by hyperinflation to levels that will buy them a few loaves of bread, or perhaps a bag of rice.

Some never return from the brutal pits, whatever deaths they met there not registered, their bodies never officially buried. Among the missing are photographer Wilmer González, who both chronicled the mines and worked in them.

In the region, many who are not directly digging for gold are dependent on the gold economy to survive. Every day a steady stream of passenger cars head to the mines loaded with jerrycans of diesel, many driven by white-collar workers.

“I have no choice if we want to eat – I haven’t been paid for months,” said Lucia, a primary school teacher who twice a week makes the 18 hour round trip with her husband and two small children, risking malaria and violence for a small markup that will keep a roof over their heads, and the most basic of meals on the table. She asked not to use her real name for fear of losing her job.

Once a supporter of Hugo Chávez, she lost faith in the government as the economy collapsed around her once-prosperous family, destroying her husband’s blue collar factory job and turning her teaching post into a voluntary one.

“This has led us to do things we could never have imagined, selling cheese, dealing hard currency. Then when we didn’t have any other way to make money we decided we had to sell diesel [to the mines],” she said.

The lure of the gold buried under the forests of eastern Venezuela is centuries old. Walter Raleigh sailed up the Orinoco river past the current-day site of Puerto Ordaz in search of the mythical El Dorado, city of gold, which was never found but lent its name to an undistinguished town on the road to Brazil.

In recent decades, as Venezuela swam in the easy profits from oil, the gold mines seemed more like historic curiosity than going concern. The town of Callao, a regional hub and popular tourist spot, was known mostly for its carnival festivities.

Visitors strolled down quiet colonial streets, where shops sold handmade gold jewellery, and one firm had a concession to run a large, modern mine. Today no one would visit for fun.

It become an unuruly and dangerous jumping-off point for the reinvigorated mines, its streets lined with gold dealers and packed with miners. The crowds occasionally part for a luxury SUV with blacked-out windows and an armed escort, the closest most in the area will get to seeing the power behind the money.

The workers come thinking they will only stay a short time, then leave with a small fortune, but most make a pittance and spend much of it locally, on food and drink or in brothels. In the area there is a saying: “What the mine gives, the mine takes away”.

Those who reaps most profits are largely invisible. Perhaps the most remote, connected through a tangled chain of intermediaries, is the government itself, after it discovered in the mines a way to turn fast-devaluing bank notes into pure gold.

The trade is funding Maduro’s government as petrodollars dry up. Venezuela has the world’s largest oil reserves, but the industry has crumbled under the weight of corruption and mismanagement. The state-owned firm PDVsA, once a cash cow for Caracas, can now barely pay its bills.

“I only accept PDVSA jobs where they pay me upfront, otherwise I don’t get paid” said one executive at an oil services firm in Puerto Ordaz.

But the government’s need for funds has not diminished with oil production, and so every month trucks trundle through Puerto Ordaz carrying boxes of bank notes heading for the mines. Paper money has been abandoned for digital payments in most of Venezuela, but in mines beyond the reach of cellphone coverage and without power supply, hard cash still reigns supreme.

It is exchanged for gold, which is then shipped overseas, including to Turkey, earning hard currency for the government, an investigation by Reuters found. That makes the area particularly valuable, and particularly tense.

Guaidó has alarmed even his allies by flirting with the idea of a US intervention, which in the east would fatally disrupt the delicate power balance between local gangs, guerrillas and the corrupt arms of the state security forces.

“At the moment we have a pax mafioso,” said Peraza. But as soon as you have a confrontation – as soon as you break the pact – there will be anarchy. This is what would happen with an invasion.”

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.