Troubled Waters:

Nuclear Submarines, AUKUS and the NPT

International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) Australia

(July 6, 2022) — In September 2021 the Australian, UK and US heads of state announced a new partnership “AUKUS” and their intention to assist nuclear-powered submarines for Australia. The Australian Government is currently undergoing an 18-month scoping period on this proposal.

ICAN Australia has launched a new report ahead of the tenth Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in August 2022, Troubled Waters: Nuclear Submarines, AUKUS and the NPT.

Troubled Waters critiques the Australian government’s proposal to acquire nuclear-propelled submarines and proposes closure of the loophole in safeguards under the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) that would be exploited for the plan to go ahead.

Former Head of Verification and Security Policy Coordination at the International Atomic Energy Agency, Tariq Rauf, argues that the planned submarine deal would pose a threat to nuclear non-proliferation and that states parties to the 1970 NPT should consider amending the treaty’s operation to prevent all non-nuclear-armed states from gaining access to nuclear propulsion technology.

Of key concern is the threat Australian nuclear submarines pose to the NPT, the broader safeguards regime and peace in our region. Further, Australian nuclear submarines would increase nuclear dangers and are an unnecessary, precedent-setting and retrograde step.

Troubled Waters contains writing by Australian and international safeguards, non-proliferation and legal experts including:

- Tariq Rauf,The challenge of nuclear-powered submarines to IAEA safeguards.

- Trevor Findlay,The AUKUS submarine project and the nuclear non-proliferation regime.

- Richard Tanter,Nuclear-powered submarines for Australia — stepping back into the Anglosphere and into a new Asian arms race.

- Monique Cormier,Implications for the international legal regime.

- Talei Luscia Mangioni,Pacific perspectives on proposed AUKUS nuclear-propelled submarines.

- Muhadi Sugiono,Indonesian concerns about the proposed AUKUS nuclear-propelled submarine deal.

Further, the new Australian government has the opportunity and mandate to provide enduring certainty of the government’s commitment to nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament by signing and ratifying the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

Troubled Waters was first published in January and revised in July 2022.

INTRODUCTION

Marianne Hanson and Gem Romuld

Against a background where the proliferation of nuclear weapons is an ongoing concern, the Australian government in September 2021 announced AUKUS, an expanded trilateral security partnership with the UK and US governments. A key element of this agreement was the proposal to deliver eight nuclear-powered submarines to Australia, vessels which if they eventuate, are likely to utilise significant quantities of highly enriched uranium (HEU).

The Australian government which negotiated AUKUS was voted out of office in May 2022, and it is not yet clear from the new Labor government whether the submarine deal will go ahead or what form it might take if it does eventuate. It is nonetheless important to address now the proliferation concerns associated with the proposal, and to encourage the new government to re-think this decision.

The Prime Minister at the time seemed remarkably sanguine about acquiring nuclear-powered submarines, but many observers did not share this complacency and voiced their concerns about the domestic and international ramifications involved.

The extent of disquiet was clearly evident when the Australian Joint Standing Committee on Treaties invited responses to the agreement. Despite the public being given less than a week to register their views, 104 submissions were received, and these were overwhelmingly against the nuclear submarine proposal. Several individuals and organisations expressed unease about such a profound reorientation of Australian security, defence, and nuclear policy [1].

Others questioned the need for nuclear-powered submarines in the first place [2]. Such vessels are viewed primarily as a means of projecting power at a distance, that is, close to China’s coast in tandem with US war-fighting strategies, rather than as vessels suited to defending Australia’s own coast; as such, a

… But the proposal nonetheless breaks an existing taboo and sets a precedent where other states will use the same logic to acquire nuclear material and sensitive technology.

return to conventionally-powered submarines is seen as a more appropriate and cost-effective strategy. Unusually, former prime ministers from both parties of government also spoke strongly against the plan.

There is also the view that acquiring nuclear submarines could entail an escalation in Australia of many things nuclear: more nuclear engineers and capacity in and out of the Australian Defence Force, and further nuclear military enmeshment with the US and UK.

The majority of Australians share an aversion to nuclear weapons and power, and there is a concern that the case for nuclear powered submarines could be used to soften the public on the eventual stationing or storage of foreign nuclear weapons on Australian soil.

The most immediate concern however is the proliferation risk posed by nuclear-powered submarines. Australia has long supported nuclear non-proliferation efforts. It has championed domestic and international programs to reduce and remove HEU from civilian uses worldwide, and it claims to support a Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty.

But acquiring large quantities of HEU — one analyst suggests that there could be up to 20 nuclear weapons’ worth of HEU on each submarine [3], on mobile platforms for several decades outside of usual IAEA safeguards and scrutiny —jeopardizes non-proliferation efforts and fissile material security [4].

Closing the Paragraph 14 Loophole:

An Urgent Non-proliferation Measure

The Australian decision was made on the assumption that it would be permitted to divert nuclear material for what would be, essentially, a non-proscribed military purpose, by utilising Paragraph 14 of the IAEA’s Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement (CSA).

The ‘loophole’ of Paragraph 14 is seen by many as problematic because it potentially allows non-nuclear weapon states to acquire nuclear material which would be removed from IAEA safeguards. This poses a risk to the nuclear non-proliferation regime which relies not only on suppressing demand for nuclear weapons but also on controlling the supply of material which could be used to produce these weapons.

If the proposal goes ahead, Australia will set a risky precedent: it would become the first non-nuclear weapon state to be given this highly sensitive nuclear technology. And because, under the existing agreement, the uranium to be used is likely to be weapons-grade, the plan increases the risks to non-proliferation even further.

HEU is the most suitable material for ready and rapid conversion into a nuclear bomb. While removing HEU from a submarine would not be an easy process, the possibility of diverting such material for weapons purposes cannot be ruled out.

The Prime Minister at the time reaffirmed that Australia will not acquire nuclear weapons. But the proposal nonetheless breaks an existing taboo and sets a precedent where other states will use the same logic to acquire nuclear material and sensitive technology. Indeed, since AUKUS was announced a number of countries, including Iran, have indicated that they too would like to utilise the Paragraph 14 loophole.

ICAN Australia therefore strongly supports a campaign to ‘Close the Paragraph 14 Loophole’. The Tenth Review Conference of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in August 2022 provides an opportune moment to urge governments around the world to strengthen non-proliferation efforts.

UK nuclear submarine.

Why the NPT and Why Now?

Raising these proliferation concerns now is an important task. The AUKUS submarine plan is still in its initial 18-month planning phase, and the precedent has not yet been established. The prospects for curtailing the plan are greater since the new Labor government was elected in May 2022.

While in opposition, the (now) Prime Minister Anthony Albanese had put conditions on Labor’s support for the proposed nuclear powered submarines: no requirement for a domestic civil nuclear industry, no acquisition of nuclear weapons, and compatibility with the NPT. But as we show in this report, the submarine proposal if it goes ahead is likely to have a deleterious impact on the NPT and the non-proliferation regime more generally.

The upcoming NPT Review Conference is therefore precisely the right forum at which to raise this issue. It has the mandate to strengthen rather than weaken the global non-proliferation regime by moving to close the Paragraph 14 loophole. We believe that Australian acquisition of nuclear submarines would be an unnecessary and retrograde step, and we urge the new Labor government to consider alternative types of submarine technology.

We hope that this Report will encourage active and critical engagement by the international community. Efforts to advance nuclear non-proliferation are of high importance and in a context where the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons has entered into force and is gathering support, the proposed step towards, rather than away from, utilization of weapons-usable fissile material and technology carries unacceptable and unnecessary risks.

The proposal to ‘Close the Paragraph 14 loophole’ is gaining support from several states and civil society groups. We note that even if the safeguards loophole is not definitively closed at the upcoming Review Conference, if many states raise concerns about the proliferation implications of the proposed nuclear-powered submarines, these plans can be shelved before they have progressed and are harder to change.

This Report therefore assesses the following issues:

Tariq Rauf makes a comprehensive case against any further development of naval nuclear reactors. As the former Head of Verification and Security Policy Coordination for the IAEA, he calls on states at the upcoming NPT Review Conference to find ways to close off the Paragraph 14 loophole, arguing that “now is the time to further strengthen the effectiveness and improve the efficiency of the IAEA safeguards system, not to weaken it and not drive a fleet of nuclear-powered submarines through it.”

Trevor Findlay details the impact that the nuclear submarine deal could have on the Non-Proliferation Treaty, and how the military-to-military transfer of enriched uranium to a non-nuclear weapon state like Australia presents a problem for IAEA verification. He reminds us that the deal could pave the way for a variety of other non-nuclear weapon states — some with possible [or potential] proliferation motivations — to acquire nuclear materials and to avoid compliance with safeguards.

Richard Tanter surveys the broad strategic implications of enmeshing Australian defence capabilities more closely into American and British military postures, and addresses the risk that AUKUS might serve to exacerbate regional tensions.

Monique Cormier raises questions of whether a non-peaceful nuclear activity — that is, the use of enriched uranium for fuelling a submarine — contradicts the NPT’s object and purpose, and whether this is a legitimate action for Australia, a state that otherwise professes to be a champion of nuclear non-proliferation, to take.

Talei Mangioni brings an important Pacific voice into the debate. She surveys the impact that the submarine announcement has had on Australia’s South Pacific neighbours, for whom the humanitarian impacts of nuclear tests remain of grave concern. Her analysis reminds us that Australia has paid little attention to its South Pacific neighbours in recent years, and that it underestimates the intensity of the anti-nuclear sentiment in the region.

Muhadi Sugiono notes that AUKUS has already created proliferation, strategic, and political concerns among some of Australia’s closest neighbours in South-East Asia, and argues strongly for closing the Paragraph 14 loophole.

Cooperating with the IAEA in the area of nuclear safeguards and verification strengthens the complementarity between the NPT and the new Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, as affirmed by the Vienna Declaration [5] adopted by the first Meeting of States Parties to the TPNW in June 2022.

Australia has often raised the need to ensure such complementarity between these treaties and upholding existing IAEA safeguards, rather than weakening them by acquiring nuclear submarines, is an obvious way to do this.

Finally, the best assurance the Australian Government can give of its commitment to nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament is to sign and ratify the TPNW, in line with its pre-election commitment to do so. In the context of Australia’s pursuit of nuclear-powered submarines, and the concerns of our neighbours in South East Asia and the Pacific, such a commitment will be important for building peace and security in the region.

Marianne Hanson is Associate Professor of International Relations at the University of Queensland and ICAN Australia Co-Chair. Gem Romuld is the Director of ICAN Australia

Nuclear-powered Subs for Australia

– Stepping Back into the Anglosphere

and into a New Asian Arms Race

Richard Tanter

The Australian government’s announcement in September 2021 of a new set of military agreements between Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom was a surprising, retrograde and risky step.

For many Australians, the idea of the UK being of any serious strategic importance to Australia, more than 60 years after that country withdrew from its military positions ‘East of Suez’, was a step back in time to the formation of the Australian state as part of the British Empire in 1901.

Just as Australians are slowly beginning to recognize the realities of their location in Asia, a deepened alliance with the United States and a post-Brexit reboot of the UK has put the ‘Anglo’ back in the racialised identity that makes up the Anglosphere.

The most well-known aspect of AUKUS is the agreement with the US and the UK to supply Australia with nuclear-powered submarines — or more precisely, with nuclear-propulsion technology.

While much is unclear about this proposal and much about it problematic in terms of weakening the nuclear non-proliferation regime and exacerbating the strategic arms race in Asia, what is clear is that the decision will have major strategic consequences for Australia, and from the perspective of China, potentially existential consequences.

The prelude to AUKUS — by just a matter of minutes — was the cancellation of a 2016 Australian contract with a French government-owned shipbuilder for eight French conventional diesel/electric-powered submarines, expected to be worth more than A$100bn.

Under AUKUS, the US will allow the export to Australia of naval nuclear power technology, either directly or by licence through the UK (with the latter making up an Australian and US subsidy to post-Brexit Britain).

Almost everything else about the submarines — what type they will be, what their operational capabilities will be, which country will build them, and when they will be delivered — is to be decided following a review to be completed in 2023. Effectively, the AUKUS submarine decision amounts to a $100 billion plus blank cheque.

Nothing is known about the next Australian submarine except for one fact: nuclear-propulsion. Nuclear naval reactors are, the Australian government has stated, required for long-range, long endurance, high-speed capability operations in waters distant from Australia’s immediate neighbourhood

The two most important questions to ask about any major weapons system platform concern its primary strategic purpose: what strategic need is it intended to meet, and what are the strategic consequences of that acquisition?

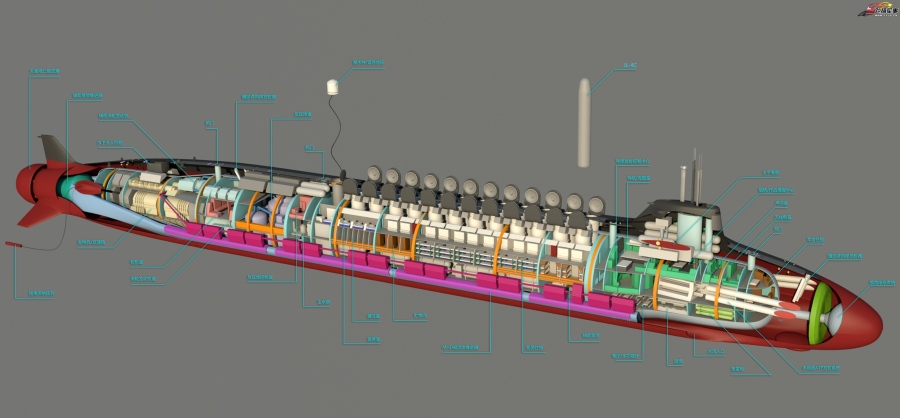

Schematic of a Chinese nuclear-powered submarine.

In the case of what will become the largest Australian military purchase ever, the answers to these basic strategic questions are deeply troubling, and both involve China.

Whether based on the US Virginia class hunter-killer submarines or the UK’s troubled Astute class attack submarines or some new design, the vessels will be more than double the tonnage of both Australia’s current submarines and their now-abandoned French replacements.

The very long range and great size of the likely US or UK nuclear submarines means that they are not principally designed for operations in Australian waters and their approaches -the traditional and understandable defence concern for Australian naval planners.

For the most part, large, fast nuclear-powered submarines are not the most appropriate choice for the relatively shallow waters of most of littoral Southeast Asia and the waters north and northeast of Australia.

Australia’s prospective nuclear-powered submarines will in fact be primarily designed for operations in distant waters working in concert with the US Navy in two key types of operations against China.

One mission will be to join US hunter-killer submarines in protecting US-led aircraft carrier taskforces attacking Chinese air, naval and ground targets from the Pacific or the South China Sea. Since 1945 the US has been able to move on to the offence with impunity by bringing its carrier taskforces in range of mainland Asian targets.

In the past, there was little China could do to respond. Now, with Chinese coastal defences significantly improved, the US will have to proceed more cautiously, hopefully protected against Chinese submarines by a phalanx of US and coalition anti-submarine warfare assets, including hunter-killer submarines. Australia is offering to make a marginal contribution to such an attack on the Chinese homeland.

The second, even more serious mission involves a marginal Australian contribution to an even more dangerous attack on Chinese military capabilities in time of war: hunting, in concert with US attack submarines, Chinese nuclear ballistic missile submarines that make up the core of their survivable nuclear deterrent force.

China’s hope is that its nuclear ballistic missile submarines hiding in the deeper parts of the South China Sea or in the abyssal trenches of

the western Pacific will be hard for the US and its allies to find and destroy. In contrast, China’s land based missiles are highly vulnerable to a US nuclear first-strike and to interception by US missile defence systems.

China hopes that even with that vulnerability to a US first strike, its nuclear missile submarines would provide the basis of a retaliatory second strike — and thereby deter the US from any nuclear attack on China.

Whatever one’s doubts and objections about the validity of deterrence theory generally, there can be little doubt that China, like the United States, takes the deterrence of nuclear attack by the possession of nuclear weapons that can survive a surprise attack very seriously.

There are of course a number of other important strategic uncertainties and concerns involved in this decision. Planning for long-range Australian submarine missions against Chinese targets assumes unimpeded passage through the waters of countries to Australia’s north — an assumption that in itself indicates Australian arrogance and disregard for its neighbours in the South East Asia Nuclear Weapon Free Zone.

Moreover, a number of senior Australian defence experts and former senior officials see the plan as driven by domestic political and alliance management considerations rather than by careful and balanced assessment of Australia’s primary strategic defence needs.

Others see the program as hopelessly unrealistic in terms of budget and defence procurement capability, and doubt Australia will in fact acquire the promised nuclear-powered submarines.

Apart from the likely prohibitive costs and the politics-driven wrangling about which country and company will build what where, US and UK nuclear-powered submarines are as a matter of policy fuelled for their lifetimes by highly-enriched uranium(over 90%-enriched uranium).

This is concerning for three further strategic reasons:

Firstly, Australia has no civil technology base to maintain and operate nuclear power plants of any kind, let alone naval nuclear reactors for sub-surface combat conditions.

Secondly, as Monique Cormier and Trevor Findlay argue cogently elsewhere in this report, while export of naval nuclear reactors is not prohibited under the Non-Proliferation Treaty and IAEA safeguards, the planned export of highly-enriched uranium to power the submarine reactors undermines the spirit of nuclear non-proliferation embodied in the South Pacific and South East Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zones embraced by all of Australia’s neighbours.

And thirdly, since previous requests to the US for the same nuclear-propulsion technology from Asian allies more important to the US than Australia such as South Korea have been refused, this US policy towards Australia will be diplomatically unsustainable. The inevitable result will be an escalating naval arms race in East and Southeast Asia — a development that in itself works against the enduring defence interests of all concerned.

Professor Richard Tanter works with the Nautilus Institute and teaches on nuclear weapons and on Australian foreign policy at the University of Melbourne. He is a former president of the Australian board of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons.